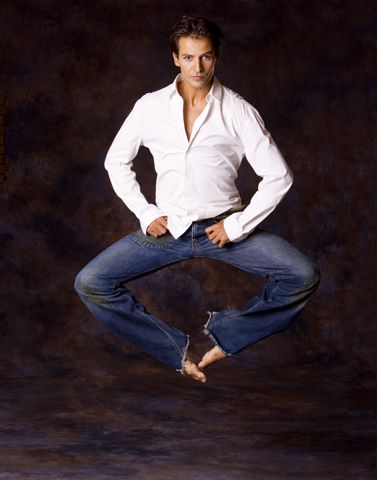

Juanjo Arques is the second of four children, whose mother was a seamstress working from home, and whose father put in 12 hour shifts at a paprika powder factory. In a village in southeast Spain, his childhood home was draped in lengths of fabric, patterns, cut-out cloth pieces and redolent of the powerful scent of paprika that clung to his father’s uniform. His parents have always been supportive of what he wanted to do, as is his whole family now, although the others have all remained nearby to home and mostly don’t follow the dance world very closely. From when he was a little boy, Juanjo always danced whenever there was music. His village, “like all those Spanish towns,” he says, had a folkloric music/dance group. He took part in the local one as a child and picked up the fairly simple steps quickly.

Before long, the teacher of his group advised his parents that he should get dance training at the Conservatorio de Danza in the nearby town of Murcia. The school day was long, 9 to 12:30, a lunch break at home to 3:30, then more classes until 5:30.

After that, from about 11 years old on, Juanjo would catch the train into town for dance lessons, only returning home at about 9 for a late Spanish dinner. At the conclusion of his Conservatorio training, Juanjo joined the Ballet Victor Ullate in Madrid.

Having reached soloist level there, Juanjo decided that he wanted to expand his repertoire, especially in the classics of ballet. When an audition was being held for the English National Ballet, he took a 6 am flight to Britain, tried out and came home that evening. A short time later he heard he had been accepted and moved to London, eager to learn the language, of which he knew very little. It was a big change, a very different climate and culture. English pronunciation was especially hard, and he felt isolated at first, but he knew it was a good opportunity, and after 3 or 4 months he equilibrated.

Toward the end of his fourth year, Juanjo was getting cast in principal roles in such ballets as Romeo and Juliet and Nutcracker, but he says, “It wasn’t my passion. I was happy in soloist roles.” By this time, he also was again feeling the urge to broaden his vocabulary and had personal reasons for wanting to come to the Netherlands as well.

So when Juanjo was accepted as a soloist by the Dutch National Ballet, a company with a much more mixed repertory, it was “perfect.”

While at the DNB, Juanjo’s attraction to choreography grew. It had been there in latent form since childhood. As a kid, he had a Walkman tape player and somehow acquired a recording of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. He was used to classical music from the Conservatorio, and spent a summer visualizing the music in steps he was learning in dance class. “Lots of turns,” he says because that was what he liked to do best.

There also was a choreography class in his last year at the school. Because he was combining the program of two years in one, he had to create and perform “a choreography” before a jury of teachers. By that time he had seen rather more ballet and had a wider vocabulary of steps. As to theme, “I always liked dark,” he says and chose the music to The Omen. Satanic rites!

The choreography class was more historical than practical, and remembering that effort now, he can see that he didn’t yet have the tools to do the job very well. But his interest in making dances kept growing. “It was like I had a world full of things to talk about and no vocabulary.” That interest was further piqued by choreographic workshops at ENB and DNB. Gradually his desire to choreograph, fed on Balanchine and other American videos, became a hunger that outgrew his wish to dance himself.

The choreography class was more historical than practical, and remembering that effort now, he can see that he didn’t yet have the tools to do the job very well. But his interest in making dances kept growing. “It was like I had a world full of things to talk about and no vocabulary.” That interest was further piqued by choreographic workshops at ENB and DNB. Gradually his desire to choreograph, fed on Balanchine and other American videos, became a hunger that outgrew his wish to dance himself.

“I noticed as a choreographer a few years ago,” he says, “that I’m not very comical, I’m dramatic unconsciously. My movements translate emotions, sensuality, feelings of intimacy.” Looking back over the past couple of years, he sees that his pieces “are all about relationships, what makes people connect. This is my talent, my strong point.”

“I noticed as a choreographer a few years ago,” he says, “that I’m not very comical, I’m dramatic unconsciously. My movements translate emotions, sensuality, feelings of intimacy.” Looking back over the past couple of years, he sees that his pieces “are all about relationships, what makes people connect. This is my talent, my strong point.”

As an interesting corollary of this approach, he relies for expression in his work on physical language. Excessive drama in the face distracts. It “competes with movement,” he says. Too much face, piling drama on drama, “kills the drama.” So for him the faces of his dancers need to be “more neutral, just eyes.” He is very much concerned with having the dancers be aware of what they are looking at, what they see.

As an interesting corollary of this approach, he relies for expression in his work on physical language. Excessive drama in the face distracts. It “competes with movement,” he says. Too much face, piling drama on drama, “kills the drama.” So for him the faces of his dancers need to be “more neutral, just eyes.” He is very much concerned with having the dancers be aware of what they are looking at, what they see.

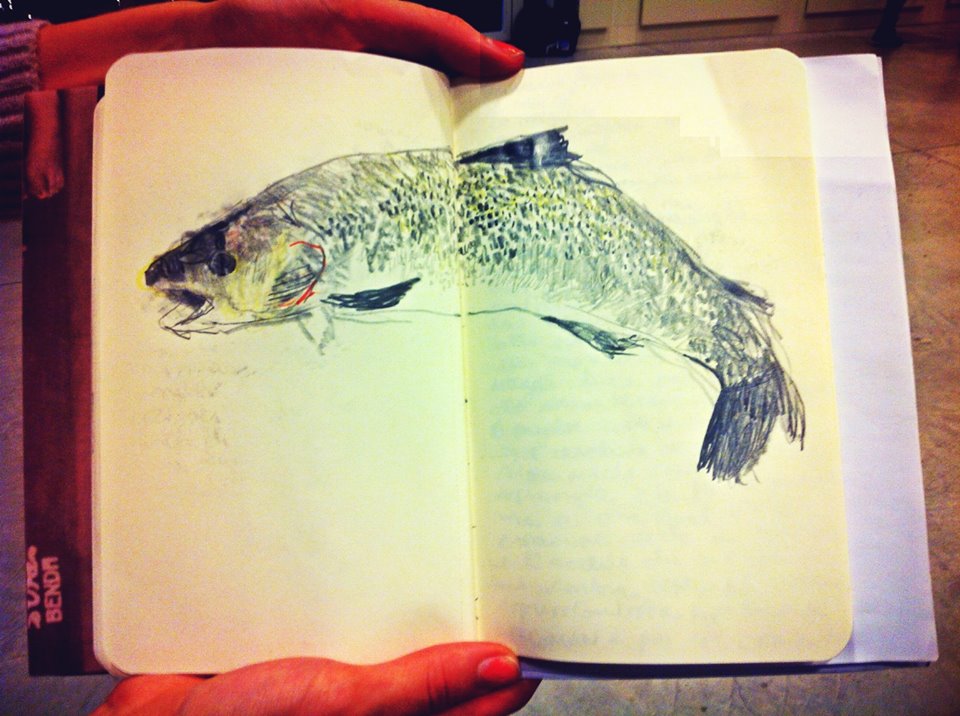

About a year and a half ago, Juanjo finally decided to leave DNB to devote himself to full time creation of contemporary works for classical companies. But he is also “interested in learning different codes” and in “being a bridge” between forms. He is currently involved in choreographing and coaching the principal actor in a play called Vaslav about Nijinsky, a Joop van den Ende production for DeLaMar Theater of Amsterdam. Likewise, he is also one of the four choreographers of a two-year, multi-city, multi-disciplinary European project entitled Performing Gender—in the course of which the drawing of one collaborating artist portrayed Juanjo in the form of a trout: flexible, changeable, strong.

About a year and a half ago, Juanjo finally decided to leave DNB to devote himself to full time creation of contemporary works for classical companies. But he is also “interested in learning different codes” and in “being a bridge” between forms. He is currently involved in choreographing and coaching the principal actor in a play called Vaslav about Nijinsky, a Joop van den Ende production for DeLaMar Theater of Amsterdam. Likewise, he is also one of the four choreographers of a two-year, multi-city, multi-disciplinary European project entitled Performing Gender—in the course of which the drawing of one collaborating artist portrayed Juanjo in the form of a trout: flexible, changeable, strong.

Experimentation is in Juanjo’s nature. He does a lot of workshopping, and indeed the piece he’s now making with the Whim W’Him dancers began in a series of workshop exercises. He chafes at the ordinary balletic stage constraints on audience/dancer contact. “I am not interested to continue with that too easy, perfect beauty,” he says.

It’s a different, more complex and layered sense of beauty he is after.

For a taste of how Juanjo’s new piece for Whim W’Him is developing—

Juanjo Arques for Whim W’Him on Vimeo

Then come watch the final result!

January 17, 18, and 19 at Cornish Playhouse (formerly Intiman Theatre)—

https://mys.iqs.temporary.site/event/instantly-bound/