The dancers’ mys.iqs.temporary.site pages each feature a statement they have made about dance. Andrew McShea‘s reads: “There’s something so paradoxical about dance. Using opposition is something we, as dancers, are taught early on in our training. Rooting down, while growing upwards. Making it look effortless, while swimming in the rigor of it. Finding the balance of freedom of expression, while keeping the clarity and purity in the structure. In this way dance reflects life.”

The paradox and the oppositions of dance have never been more reflective of life than during this pandemic, when, as Andrew puts it: “Everyone in a weird zone, re-evaluating ourselves, especially socially. We were free in a social setting, spontaneous. No more. There’s not a lot to be planned now. The core of ourselves—of myself has been shaken up. It’s not what I expected—a very specialized kind of growth period.” He continues, “I had a bit of a know-it-all attitude. I like structured planning of my life,” though “Last year I was more free, sent caution to the wind. I thought I’m young, why not?” But then Covid 19 hit. “The pandemic has knocked me off my high horse. Everything—work, play, relationships, personal life.” All he thought he knew vanished, or went into hibernation. It brought on what he calls, “a very evaluative state of mind” causing him to mull over “the social nature of our isolation.”

Andrew joined Whim W’Him early this summer, along with Ashley Green and Michael Arellano. Ashley he had known from Point Park University. Michael he met at an earlier Whim W’Him audition and had friend-of-a-friend connections with him as well, but they got much better acquainted when the two agreed to drive out together from the Midwest. It was a long trip, “35ish hours” to Seattle, where the three have shared an apartment since July 1st.

I asked about what good, if anything, might come from the pandemic. He said “a happier climate where we’re pushed in to rediscover approaching social situations. We’ll have to relearn how you meet people after so much isolation.” He finds it intriguing that, compared to his housemates, “I was more social in general before, now less than the other two.” We talked about how much less superficially you learn to know the people you live with in this new sequestered world. The Whim W’Him dancers have always been a close-knit bunch, but Andrew was struck by the ease of transition into his future artistic home. Even before coming out to Seattle, the newcomers were attending Zoom meetings—which included ice-breaking games introduced by artistic director Olivier Wevers to help everyone get acquainted with each other’s personalities and interests, as well as more serious discussions. The most recent additions to the company also had become involved in the various projects of setting up the IN-WITH-WHIM platform, including being interviewed by dancers already in the company. All this activity, observes Andrew, “got us over the awkward getting-to-know-you phase, so that by the time we saw each other in the same room, it was ‘Oh, it’s so great to meet you in person!’ The connection was quick and smooth.”

There was a hiatus in which Andrew and the other two settled in and explored their new environment, transformed just then by the summer protests and Whim W’Him’s own efforts to help marginalized voices to be heard. In late August work started on the fall’s dance offerings—all to be presented on film. Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s GRASSVILLE was the first. Work began briefly in a Seattle studio, but Annabelle was in Amsterdam, while the dancers, though in the same room, had to remain distanced and to wear masks. The circumstances were not appropriate for what Annabelle had intended, so she quickly switched gears, and the dancers worked from home.

Despite the fact that Annabelle was still communicating from her own flat some 6000 miles away, ‘That was nice, more intimate,” says Andrew. “She could give directions, ‘roll over on the couch,’ ‘Look toward Ashley,’ and she could demonstrate.” He was very impressed at how light-hearted, calm and “giggly” Annabelle was. She seemed to be “never stressed.” And she could supervise the filming via zoom, film within film.

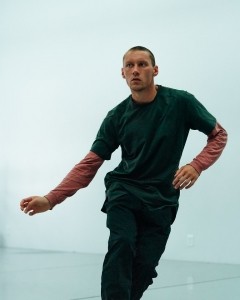

Mike Tyus and Madison Olandt’s Elsewhere was the second film made. This time all the major players were on the spot. Creating the piece (though dancers wore masks until the actual shooting) could proceed much more “as we know it.” Andrew felt rusty. It had been many months since he’d been able to flat out dance in a big studio space, but it was very stimulating to have the two choreographers and their artistic assistant Joy Isabella Brown all there together interacting in person with the dancers.

Now rehearsal for the cinematic remake of Olivier’s This Is Not The Little Prince is well and fruitfully underway. Another post on that will follow.

Of course, this eleventh season has not been entirely easy for anyone. The pivot from stage performance to film brings its own challenges and frustrations, as well as revelations and opportunities for learning. On being asked his reaction to the switch to film, Andrew replied, ‘I love the part of dance where you’re in it with everything, giving your all for the length of the piece.’ Like many dancers, he finds film definitely more challenging. “You have to go in and out of character and energy. It’s much more tiring. Many movements, even tiny sequences have to be done again and again. There are lots of repetitions and different shots.” Andrew recalls how he once wanted to be an actor. Then he worked on a film project in high school—‘it was so tedious, in and out, in and out. And that was the end of any desire to be a movie star.”

In addition, “You’re always seeing through someone else’s eye. It’s not exactly diluted, but I feel more of a body used for the film.” A piece is experienced in snippets and “you can’t see the whole.” I said, “It removes agency.” He added, “Even the choreography is part of a puzzle. It’s much more collaborative.” We talked about how by the time a work is staged, all the other parts—choreography, setting, lights, costumes, makeup—are all set. The piece then unrolls and it’s done for that performance. With film it keeps being tinkered with.

And in the end, one thinks of it as the filmmaker’s product. No accident that films are most often identified/remembered by their director’s names, even when there are famous actors and writers also involved. During a stage performance, everything else falls away, and it’s the moment of the dancers to shape it and carry the burden of what will be seen and felt in that moment. The other aspects become ancillary. That can be true of a good dance film, but the agency is much more in the hands of filmmaker and editor (who might be the choreographer). It’s not the dancers’ choices in the moment and directly in communion with the audience that makes the experience. They too sit back to watch the final product on the screen, audience members like everyone else. May be very exciting, and you may learn something about your own performance that you wouldn’t if it’s live—or even if it’s videoed in a standard way during performance. But the immediacy of live performance simply isn’t there, even when one sits in a (distanced or remote) audience of enthusiastic spectators. The dancer’s point of view is not interacting immediately in the moment of performance with the audience of that unique show. In short, Andrew concludes that making dance film is “fun” but it doesn’t hold the thrill of stage performance.

“Though,” he amends, recalling the launch of the new cinematic season, “I did have some real opening night jitters, and in the end it was so satisfying” to see the piece as a whole.

Photography credit: Stefano Altamura