Things are seldom what they seem. Even—or perhaps especially—fairy tales, with their happy-ever-after endings, are riddled with plot holes and layered with ambiguity. I’ve always wondered, for example, about the significance of the little “changeling” boy who is the object of the fairy monarchs’ squabble in the Shakespeare original of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In an age unconcerned about child labor, is he just a decorative servant coveted as a ornament of the royal couple’s respective courtly entourages? Or do Titania and Oberon have less reputable desires and intentions for him? Is he significant in himself or a mere pawn in the king and queen’s ongoing battles over love and power?

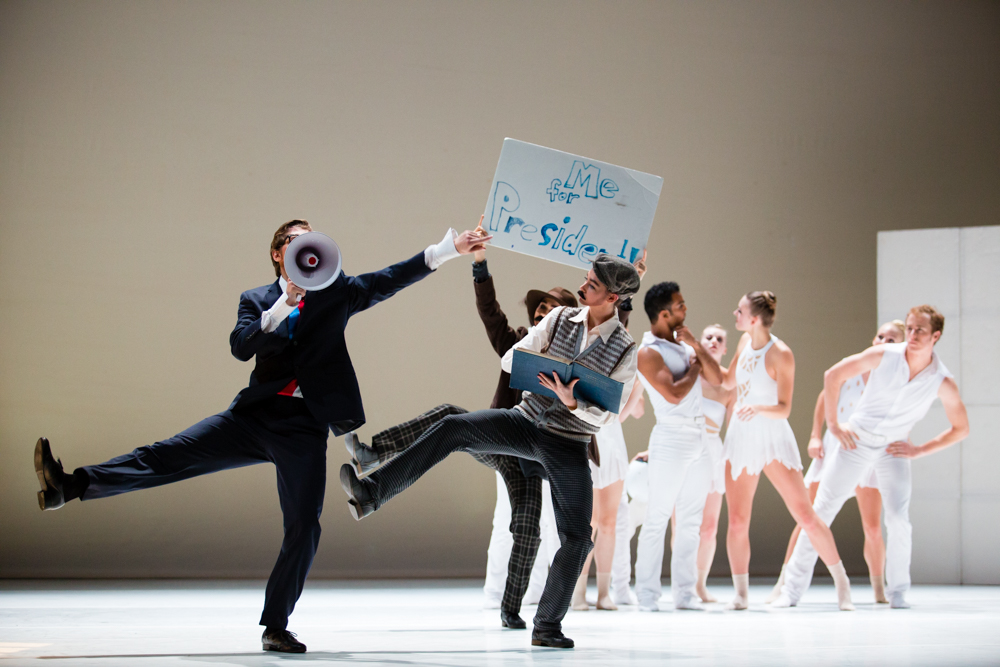

I’ve always been fascinated by theme and variations, by the retelling of old stories. Inconsistencies and oddities abound in the original Midsummer (and not just when danced versions drop some of the story lines). Such vagaries are part of the play’s mystery and charm. Its persistent attraction surely is due in part to the ways it blurs boundaries, between waking and dream, natural and supernatural. Grand Rapids Ballet’s Midsummer,* choreographed by Whim W’Him artistic director Olivier Wevers, adds new embellishments, transforming the dream into that of a young boy, Nick (Ethan Kroll). Unexpected implications come crowding in. The boy, who wants to grow up to be president, becomes Nick Bottom (one of Shakespeare’s “rude mechanicals”). In this version the adult Nick is a pompous and windy politician, who is singled out to be the plaything of the royal fairy couple. What is young Nick dreaming about his own future?

Then there is Titania, danced by the bewitching Yuka Oba. Her relationship to young Nick is confusing at best. In his dream, his silly, doting mother turns into the fairy queen But then her exaggerated adoration of him becomes a mite uncomfortable when the magically transformed donkey she falls in love with is her own son grown up. An aspect of the dream Sigmund Freud would have found as juicy as the magic flower.

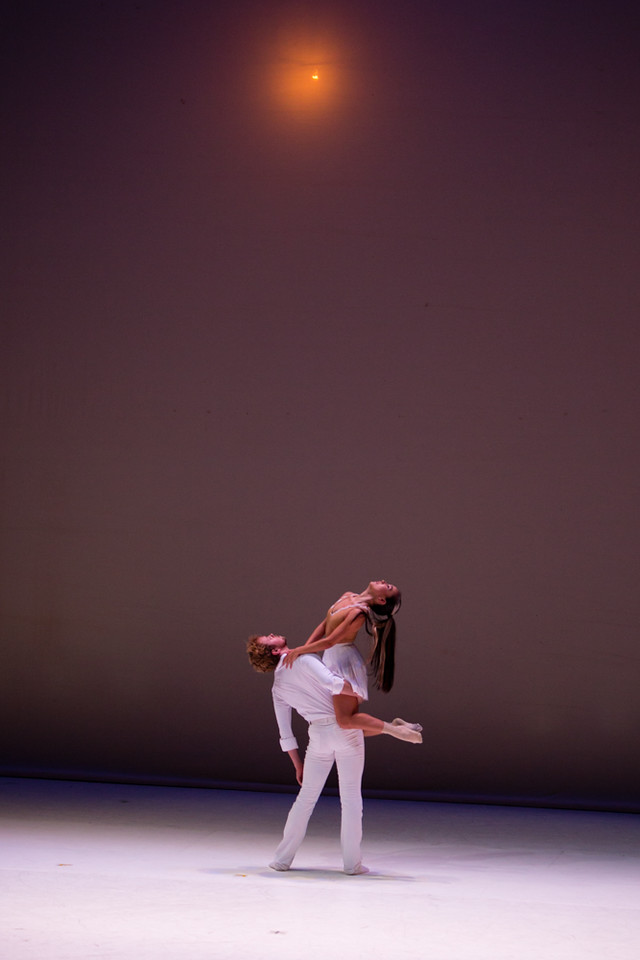

In her relation to her fairy husband, Titania is made of sterner stuff. She deliberately provokes him, teasing him and parading the coveted boy in front of him only to snatch him away. And although she is clearly bested in this episode of their unending game, the final pas de deux of the royal couple contains a gidddy mix of real love and tension, defiance and understanding.

In young Nick’s dream, Oberon himself clearly represents the absent father he apparently never knew. But the fairy king, portrayed with relish by Nicholas Schultz, is a bastard, literally kicking his servants around, maintaining order in his court by bluster and intimidation. He is, however, a complex bastard, also concerned to return the mortals to loving the ones they are meant for. Angry when Puck (out of mischief or ignorance?) casts the flower’s juice on the wrong man, Oberon makes sure the job gets done right in the end, by means of a magic fog.

Yet Oberon is very hard on his wife, observing with cynical pleasure her love affair (which he himself has engineered), then enjoying her shame when she comes to her senses and using the advantage he has gained over her to commandeer the fought-over child.

Meanwhile, although Titania’s fairies try to shield him from seeing the queen coupling with an ass, the boy buzzes about the stage, eager to witness “adult” shenanigans. At the end, as the royal pair exit hand in hand with their “son,” one can’t help wonder if future nightmares might be in store for this family. What fools for love these immortals be…

Rereading the above, I realize that it all sounds pretty dire, or at least serious. And yet the best thing in many ways about this piece is its fast-paced wittiness, its lovely combination of nuanced character, fantastical plot and sheer fun.

* * *

Another thought, on quite a different matter. It doesn’t matter how often or in what detail something is described, in words or even in photographs. Reality is different. Saying that Grand Rapids Ballet’s Midsummer’s stage setting is “white” gives no conception of this ballet beheld in person. Any fear that all that lack of color might be blank or monotone or sterile is at once dispelled by the exquisitely subtle lighting, conceived by Olivier, designed by Michael Mazzola, and executed for the Cornish Theater by Randall Chiarelli. Seeing the piece in person is like going from two dimensions to three. Or, oddly, from black-and-white to color. Such nuances make you understand what it means that white light contains the whole spectrum of the rainbow.

If you haven’t gone to see this show yet, you really should. No matter how many Midsummers you may have watched, this one is a new experience.