There is such tension in this program between external constraint and interior feeling.

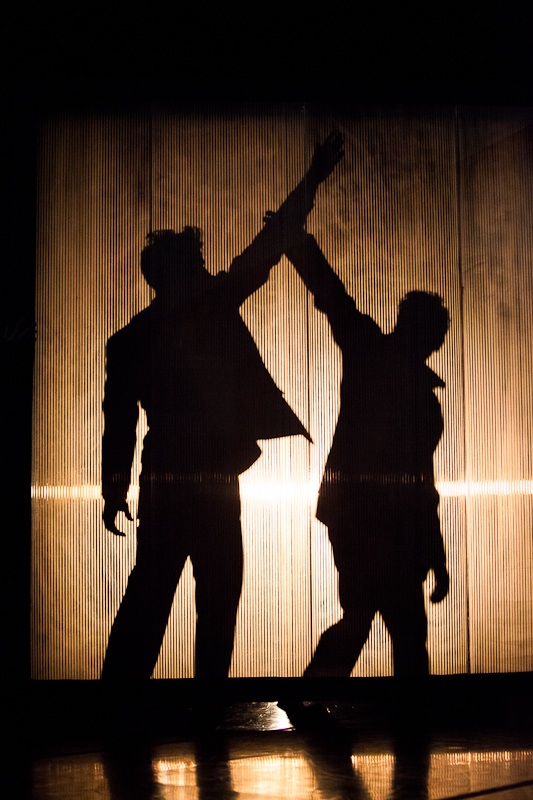

It is expressed in Approaching Ecstasy in the contrast between the flat, uncompromising angles of the unadorned stage; the rectangular set pieces; the discipline of dancers and musicians; the symmetries of musical construction; and the somber costumes, on the one hand, and in the ardent thrust of the music itself; the lungings and entwinings of the dancers—and in the mystery of light.

The brooding luminosity of Whim W’Him’s new collaboration with the Esoterics, is the creation of Jeff Forbes, a busy Portland, Oregon-based lighting designer who has lit a lot of dance (Jeff A Forbes Performance Lighting). Since high school in Anchorage, Jeff has been involved one way or another with theatrical lighting. But in those early times, though he was intrigued by all aspects of theater, his primary focus was acting.

At Lewis and Clark College, exploring the campus on his first day, he wandered into the theater department. A professor popped out of his office and said, “Hi, you want a job?” “Sure,” Jeff replied. So in addition to auditioning for and acting in plays, he hung and focused lights. Soon, quite literally, he had the keys to the department.

Jeff’s lighting skills were, as he says, “ninety percent self-taught.” Luckily he had a college roommate who knew a lot about the subject. And he learned by watching and by doing. Rave reviews for the lighting of his senior year show led to employment in various shows, which sometimes he both acted in and lit. Among other adventures, he spent a year in Wrocław at the Polish Laboratory Theatre under Jerzy Grotowski. He learned Polish, though the working language at the theater was English.

For some time thereafter, Jeff continued his parallel lives as actor and lighting designer. But eventually he realized that he could make a more secure living doing lighting. He also found he enjoyed exercising the imagination it took to light shows where the main burden of creating an atmosphere fell to the light designer, because the budget for sets wasn’t there. These were the Reagan years, when (like today) a chronic lack of money was the norm, especially in dance.

Jeff came to Whim W’Him on the enthusiastic recommendation of Michael Mazzola, who has designed the lighting for previous shows, but had a previous commitment for this May. In our first conversation, when Jeff was up here for preliminary theater rehearsals last week, he said he didn’t have a video yet, so he was watching Approaching Ecstasy for the first time. A couple of weeks before, Whim W’Him’s artistic director and choreographer Olivier Wevers had gone down to Portland and they had chosen the subdued white/dark/amber/deep blue palette. But there was lots to be factored in, such as how lighting for the unison a cappella English versions of the poetry would distinguish them from the danced Greek versions. Light plots for the dual versions of the 18 poems were not all yet in place.

I am always struck by how much lighting design for these Whim W’Him productions evolves over the week leading up to the opening. When I watched rehearsals on Tuesday, a variety of projections were being tried out on the back wall, abstract loopings, jagged geometric shapes, swirls suggestive of flowers. By last night’s dress rehearsal, projections had been pared to a minimum. It was decided that the concrete wall itself would provide most of the texture and shape. Sometimes it is illuminated in cool or warm tones behind the triple row of musicians, casting them in relief. For many of the danced sections, the wall fades into the background, as a path of light angles downstage across the darkened floor or irregular windows or spotlights appear on the floor. For the ‘Out of Their Beds’ poem, shadows of the dancers move across the wall. In the looking glass vignette, Lucien Postlewaite, as the mirror image facing away from the audience, is backlit. When reflection and reality (Andrew Bartee) join for a time, the faces of both dancers are illuminated.

The elements of design in this complicated production are simple and stark. There isn’t any set. All singers, dancers and instrumentalists, women and men alike, start out in dark suits with bowler hats. Only a tiny hint of color shows in their ties (and the costume of Kaori Nakamura, which is constructed out of men’s ties). And yet, one feels no sense of monotony. As the clothing of the dancers is shed, their skin and white undergarments glisten, while bodies clothed in dark suits recede into obscurity.

The Box, the major set piece, changes shape and radiance throughout. Sometimes it sits unnoticed in a back corner. At other times, its two opaque surfaces are whitish and mottled; at other moments it glows from within or becomes reflective itself, with lines of brightness streaking across its shiny facades.

Good dance lighting brings out nuances of the choreography, and in this production, the very uniformity of basic color and shape is artfully transformed into an infinite array of layered meanings. Everything is similar, yet nothing is or can remain the same.

Jeff Forbes’s lighting for Apporaching Ecstasy artfully plays on the restless inconstancy of life and memory, the conflict between rigid societal controls and hidden passions, as expressed in C.P. Cavafy’s poetry, in the music of Eric Banks, and Olivier’s choreography. The lighting is like a box holding the whole complex enterprise inside.