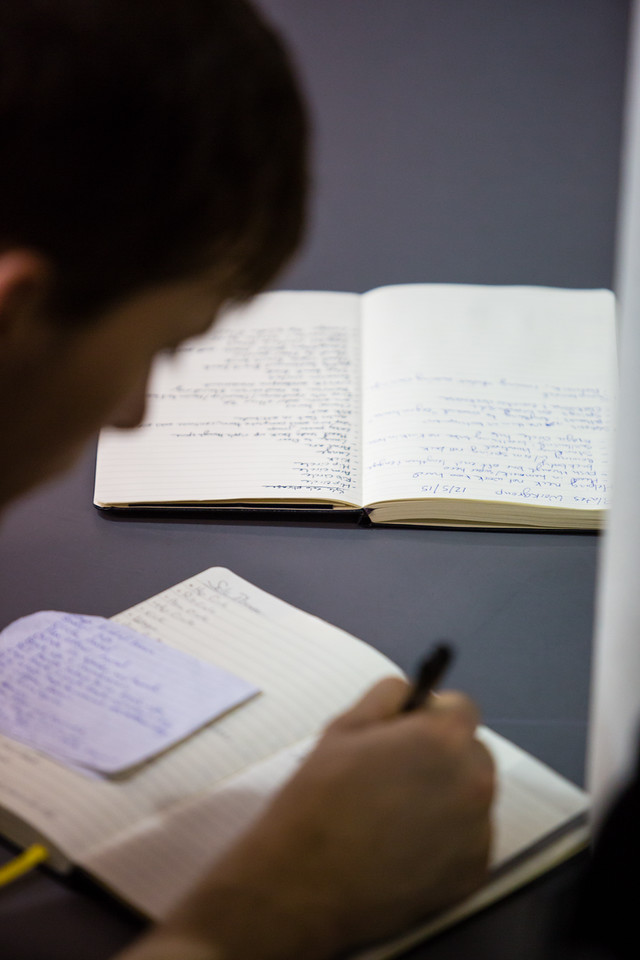

When I came in, a little late, to the first rehearsal of Mark Haim‘s new piece for IN-Spired, Whim W’Him’s January program at Cornish, the dancers were scattered about the studio with pens and paper, writing down words. The choreographer, with a glint in his eye, a playful look on his face, was watching them intently.

Mark Haim possesses infinite curiosity and a well-developed sense of mischief. He likes to laugh. “My laughs are good laughs,” he says, when one bursts out in rehearsal. “If I’m laughing, I’m happy.” He is also always thinking, experimenting, trying out combinations—of ideas, music, motion.

Normally, when working with a new group of dancers, Mark likes to re-stage a piece he’s already done—it gives him something to work from in a new context. Though he’s seen Whim W’Him performances, knows the work of the individual dancers, and has worked with Jim Kent often before, it’s always different dealing with the actual dynamics of a particular group. But he’s creating something quite new for January’s program. Despite knowing about this commission for 8 months, he says it has taken working with the dancers in the studio to crystallize what he is after this time.

Recently he’s been interested in complexity and how it can manifest in either an Apollonian or a Dionysian direction. “I think Western, specifically European, tastes in theater and dance go toward the Apollonian,” he remarks—serene, calm, well-balanced; poised and disciplined, grounded in structure and harmony. But, he goes on, complexity can also be Dionysian, spontaneous, wild, orgiastic, rejecting discipline and order—all the qualities associated with instinct and irrationality.

Mark, who talks to the Whim W’Him dancers about Apollonian and Dionysian influences, is himself capable of creating either way. In Whim W’Him Mark sees a quality of lushness that he wants to harness, to explore, to let the dancers themselves express in both directions. So he mixes things up.

For example, Mark may suddenly ask the dancers, who have each been working on solo pieces, to do them all together and then to interact in various ways. Or, as in a later rehearsal, he gives the dancers a series of 11 words (‘jump,’ ‘hinge,’ ‘collapse,’ etc.) to use as improvisational impulses. But there’s no paper or pencil this time. The dancers must recall each of their own moves, then ‘give’ them to the person on the right or left, while taking on the move of a neighbor, still keeping in mind both their own original sequence and what they’ve received from others. As if that weren’t enough, a few moments later, Mark has one and then two of the dancers use his/her first move to touch another dancer, who then does the same to a third, starting a chain reaction of individual sequences. It’s a ferocious mental workout, quite aside from the physical energy and agility required.

And yet Mark is aware of the danger of memorizing series of moves, how they can so smoothly run together that they lose individual meaning. What contemporary dance has done, he says, “is to analyze and annotate orientation toward movement, rather than toward vocabulary or steps.” Instead of looking for particular, precise positions, he urges the dancers to be aware of motivation, the body source of their movement.

“Stability and rotation, if it is weighted or twisted, bouncy or light. In time, is it rushed or indulgent? In space, close or far reaching…?” With his puckish smile, Mark observes, “If I see steps, something is wrong. I lose interest. I’m interested in the soul not the mechanism. Bach’s or Stravinsky’s music is highly calculated, but the overall effect they achieve lies in the realm of the passionate, not the rational.” In the theater too, both the choice and delivery of words and movements are essential. “It is,” says Mark, “very interesting the way art can transcend itself. You see a performance and suddenly you’re in the story.”