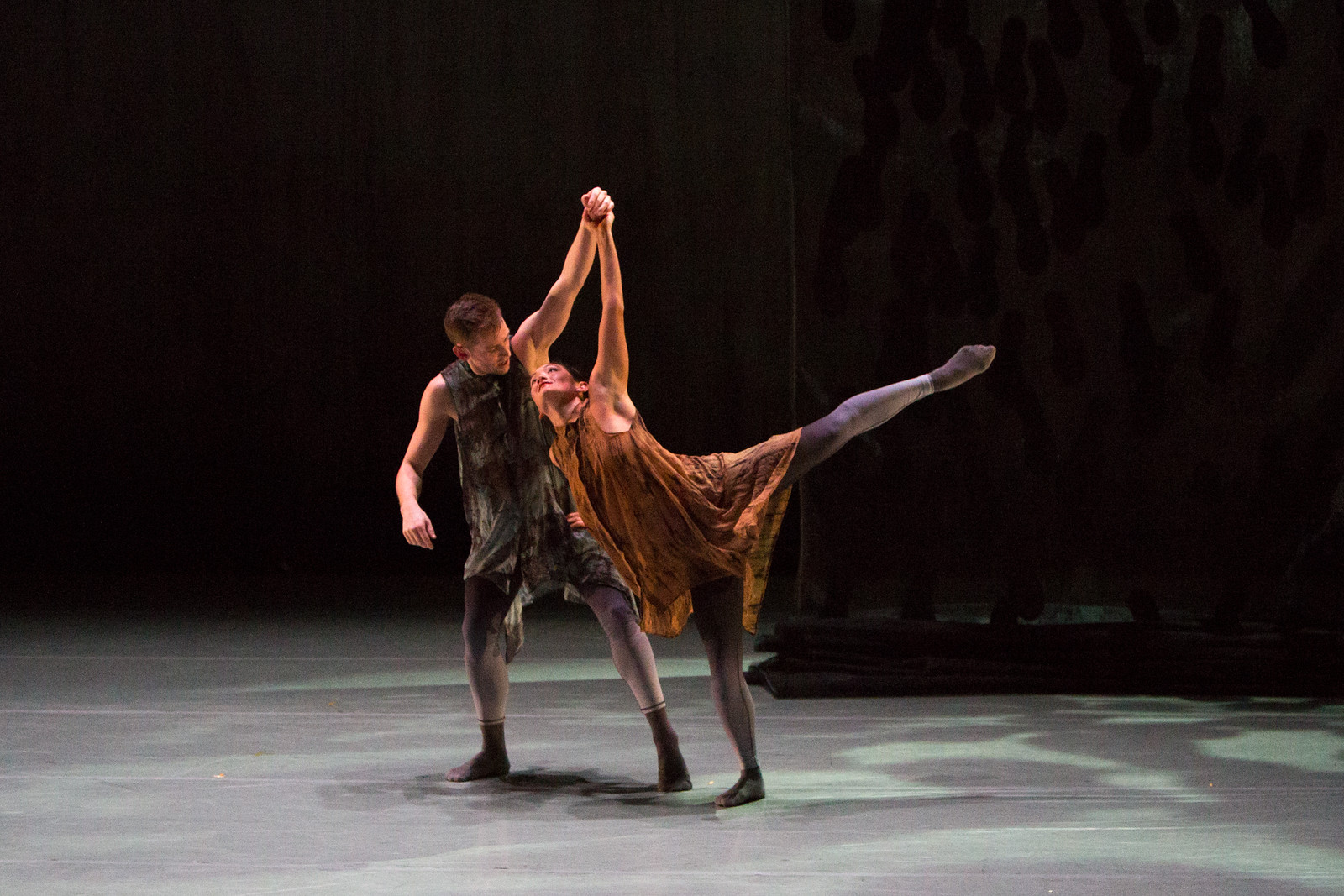

What’s always refreshing about reviews is how much difference of opinion there is, even when all the critics are positive about a show. Multiplicity of response is especially noticeable, perhaps, for the works of a company like Whim W’Him that incorporates elements of contemporary dance and of classical ballet. January 2016’s IN-spired program is case in point. As Sandra Kurtz writes for The Weekly, “Dancers in Olivier Wevers’ Whim W’Him company straddle the line between modern dance and ballet training, and performing in stocking feet seems to be an appropriate part of the compromise.” Interestingly, she adds, “I sometimes pine for a little more friction,” but concludes: “Wevers…this year At such a meeting point of old and new dance forms, certain viewers’ hearts belong firmly to one approach/style/technique, others are open to a variety of ways of looking at movement, some fall in between or don’t care what the origin as long as the result is intriguing and new, so it’s natural that each of the IN-spired pieces would have its fans. Based on reading 9 written assessments of and hearing a lot of audience commentary, I’d say most watchers had a favorite, and each of the 3 works was considered clearly the best (most interesting/most moving) by one or more commentator. In order of appearance on the program, Whim W’Him artistic director Olivier Wevers‘s Brahms and Tights was praised as “a bright, colorful work; possibly one of Wevers’ best ever,” by the Chosen Magazine blog. “For me,” wrote KUOW’s Marcie Sillman on her “And another thing…” blog, “this sprightly ballet… was the most successful dance on the bill.” The solo and partnering work was often praised as usual, though more than one viewer would like to see Olivier do more of the ensemble work of which there were intriguing glimpses (but maybe not enough?). Brahms and Tights is a pure movement creation, without plot or subtext, of which Sillman remarked: “[The piece] doesn’t have a deep message to impart; it’s a well-made, well-performed romp of movement and music. On a wet, dark, winter evening, it was just the tonic I needed.” There were plenty of kudos as well for the costumes, executed by Ronalee Wear to embody Olivier’s idea of shimmering, undersea colors. As noted by Sharon Cumberland in Seattle Gay News: “The lovely palette seemed to play as much of a role in this dance as Brahms’ passionate concerto with its lush melodies and throbbing orchestral colors.” Assorted reviewers found Mark Haim‘s Overflow “moving,” “heavy,” and “haunting.” Dean Spear of Critical Dance called it “a darker piece suggesting the flow of time and people.” According to Megan Stevenson of Seattle Dances, “a grieving, longing quality permeates” the work, which “overflows with quiet mystery,” as The Weekly’s Kurtz put it. The latter also wrote: “This isn’t a singular story of a particular relationship. Instead we watch a community of dancers, sometimes cooperating and sometimes absorbed in their own worlds.” In Spear’s words, “Overflow is a timely work, addressing and honoring not only [Mark’s] migrant parents but…today’s overwhelming European migration.…” He adds: “Corrie Befort’s set of a slowing descending transparent blackish-gray cloth with and increasing number of cutout footprints on it, was telling and added a heightened send of drama.” The gently falling curtain was universally admired, both in itself and as an essential contributor to “the emotional heft” (Stevenson) of Overflow. For Michael Upchurch, Houston-based Dominic Walsh‘s The Ghost Behind Me was “the indisputable draw on this program,” which, he continues, “was a narrative work with a central character (Kilbane) manipulated by Puppet Master (Reiter) and character with more than a hint of Death in ‘La Valse’ (Kyle Johnson).” Two Star Orchestra‘s live playing onstage of its original score for the piece got many accolades for contributing to Ghost’s “atmosphere of sinister manipulation.” As, in all 3 pieces, did the dancers, each one of whom was also singled out for critical praise. Jim Kent “physically embodied hope for me in this piece [Overflow],” reported “Lady M” of the blog Thus Spoke Lady M…, and she praised “his lithe and graceful lines through his final solo,” as Stevenson admired his “fluidity.” Justin Reiter, as the blue-bearded Puppet Master in The Ghost Behind Me captivated audiences and critics alike with his mysterious controlling of the rest of the cast, especially “Whim W’Him’s newest member, Bainbridge Island native Patrick Kilbane, whose extraordinary flex-and-ripple technique,” said Upchurch, “is a thing of wonder.“ Stevenson remarked on “the superhero presence of Tory Peil,” while DanceAlert‘s Helene, noted that Tory “did the strongest work I’ve seen from her, especially in the Haim.” Lady M was particularly impressed by her duet with Kyle Matthew Johnson, in the section of Mark’s piece “that was danced all the way downstage,” on the round apron that and remarked that “they stretched themselves from an acting perspective in a way I’ve never seen! No idea they had those types of acting chops!! They were so in the moment, so raw, so open…” “The fresh spontaneity of Mia Monteabaro,” was “particularly arresting” to Stevenson, and DanceAlert commented that “It was also great to see Thomas Phelan look more and more compelling,” while Lady M wrote, “Mia Monteabaro and Thomas Phelan performed some of the most connected performances I’ve ever seen from them in any other piece, they were so connected to their intentions.” The Whim W’Him dancers’ “prodigious technique” as a group was greatly admired too, though Stevenson of Seattle Dances brought up an interesting question when she wrote: “The synchronicity in the unison sections [of the Brahms] was always just a touch imperfect, although it didn’t seem to matter in this world that Wevers created. Simply performing the same movement at the same time did not rob the dancers of their individuality of expression.” Lady M had a somewhat different take on the issue, writing in her blog: “excited The dancers synchronicity appeared to be a bit off from each other in the first few minutes of the piece. It looked like they were feeding off of and being ushered along by the heightened energy coming at them from the almost packed house and were dancing a bit frantically to mirror each other, so they had me a bit worried at first. But once the energy settled, and they all began to breathe together as one (another element I’ve come to see as a signature of Whim W’Him, I might add), they locked in to the dance and blew my mind from that point forward!” Sillman, for her part, commented: “Kilbane, Justin Reiter and Mia Monteabaro stand out in the [Brahms] work, leaping, pirouetting, then breaking the elegant ballet lines with a sickled foot or a pedestrian stroll across the stage.” Views thus seem somewhat mixed on whether this personal distinctiveness is, under all circumstances, a virtue or a flaw. And to a teasing and tantalizing degree, the simultaneous arousal and subversion of balletic expectations come across as a definite intention of Olivier’s work. As he said with an enigmatic smile, in one of the after-show Q&A sessions (already quoted here in an earlier post), “You wouldn’t put them in a corps of Swan Lake.”

[is] extending the season to three programs, for which he’s commissioned new works from artists at the front of their profession. Lack of friction aside, this, the second of those programs, shows that Whim W’him may have a fanciful name, but is accomplishing some substantial work.”