Back at home, the 4 super-lively children were encouraged to take up new activities. Her dad started out raising his family working at a gas station, but soon got a job at O’Hare Airport and went on to become Deputy Comptroller of the City of Chicago. “He’s very political,” she says, “and taught me everything I know about charisma” which is a great deal!. Rena herself was a Girl Scout and, being very athletic, she did water polo and swimming as well as dance. Her mom, though she had attended journalism school, was a very full-time mother, keeping the kids busy and entertained—coordinating the carpools to encourage all their varied interests must have been a formidable undertaking, as Rena notes now.

Of all the activities she tried, dance called to Rena the most. It required stamina and energy, but beyond that she loved its “shape-shifting” aspect, how it led you “to overcome limitations.” And for a young girl, it was glamorous. It let her be someone she couldn’t as a 13-year-old in real life. “High heels! Running, jumping, leaping, sliding in lipstick!” She adds, “An inanimate object or an emotion” can let you “tap into something else. You can find little pockets [of meaning] in a gesture.“ For Rena, dance also combines “masculine and feminine form and getting tune with different parts of yourself.”

Familial eagerness to see and participate in the wider world has translated for into an passionate love of travel. Rena has visited, lived in and/or worked in some 20 countries so far. Beginning her studies at the Chicago Academy, she continued them at Taipei National University of the Arts in Taiwan, receiving her BFA from SUNY Purchase Conservatory of Dance. She has made dances, taught and done choreographic workshops in Marseille, France and the Macau Cultural Center in China, among many locations and companies, including 3 years at Hubbard Street Dance Chicago. She also has worked with Kyle Abraham, Bill T. Jones and David Dorfman and was a 2019 Princess Grace Award Winner for Choreography.

She is currently a dancer and choreographer at Gibney Dance in New York City. At Hubbard she co-directed with Kathryn Humphreys a program to “offer teens from various socioeconomic backgrounds—dancers and non-dancers alike—a platform to craft artistic and leadership skills, and to investigate creativity from their personal identities and backgrounds.” In fact, says Rena, “The reason I decided to go to Gibney was because of the crossover to advocacy, how Gibney had such a nice grip on that. I wanted to refine my interest in that. It was always in my bones. In high school I organized an AIDS benefit for LGBTQIA youth that raised $10,000.” Although “it’s not always how I choreograph,” she is drawn to purpose, to calls to action. “Gibney implemented that into having dancers serve in the community, whether working directly with dance or using the discipline learned in practicing it outside of dance…so dance is not just an insular form.”

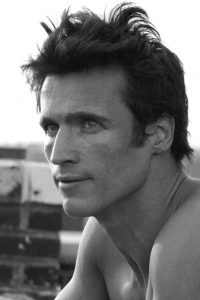

When asked about the relationship of her art and live, Rena says, “Life and art are one and the same thing, not separate realms.” Nonetheless, it’s necessary to learn “to toggle the in-between.” Later this summer, Rena and her fiancé, choreographer Manuel Vignoulle will travel to Bali where they may (or may not) exchange vows—plans for a large wedding were scuttled by Covid—and set out on a month-long backpacking venture across Indonesia. Normally, 2-3 times a year the pair take a backpacking trip abroad, either to somewhere new to one or both or where they haven’t been for some time. Rena loves to surf, Manuel loves yoga. This time they will have a month together without family or friends, “marking where we are at in our relationship after 8 years.” She says that these journeys “continue opening up my world.”

Given its two protagonists, this summer’s trip will likely will resemble critic Alice Kaderlan’s description of Manuel’s much admired 2015 RIPple efFECT for Whim W’Him: “high-energy, a continuous swirl of acrobatic action.”

But there will also be (as Kaderlan also noted) “moments of rest… and quieter contemplation.” A core desire of the couple is to find balance, in life and art, as expressed in Black/White a duet that Rena especially loves, choreographed by Manuel for the two of them some years ago. It is a strong and tender exploration of harmony in supposed opposites—“of color, sex, feminine/ masculine inside of you, yin and yang…” in Manuel’s words. They are exploring, as Rena puts it, “how to immerse yourself, and find the sweet spot, centering life and joy with yourself and with your partner and with the world, navigating through a multitude of ways, asking questions inside and outside the studio, of yourself and humanity—Who am I? Can I contribute? Can dance contribute to the world? How to reach people I would never have crossed paths with otherwise.”

The pandemic, of course, turned everything upside down, disrupting Rena’s professional and private plans as it did so many people’s, making her quest for answers more urgent than ever and posing new questions, such as whether and how the reaction to movements like BLM and AAPI might lead to real change or if they will turn out to be mostly “performative, trendy, on to the next thing.”

The piece Rena is making for Whim W’Him grows directly and indirectly out of all this searching and upheaval. She says she felt nervous before the start of rehearsals. “My head was swirling with ideas—about self/ego/narcissism; mirrors/framing; landscape vs portrait—but I wasn’t sure if they were up to par.”

In the event, however, with the dancers. “We did it together, finding landscape in a portrait and portraits in landscape.” It was “a mutual irrigation process.” Irrigated by imagination, a willingness to try anything and a lot of laughter and good will.

In different ways these images explore the duality of collectivity and individuality. “How we see ourselves in each other. How we adopt traits from each other, expressed in the mutual borrowing of physical and verbal vernacular. Fractals that make up who we are,” says Rena. “Finding looseness in control through the process of relating to others in space.”

These relationships are embodied in A Symphony of Cracks by the dancers moving as a group, like a cloud, out of which one figure rises and becomes a single entity. This repeated form allows for each of the dancers to have a concentrated moment of individual vulnerability, learning and expression. In Rena’s words the piece is a “shifting dialogue, diversifying leadership, democratizing space.”

A symphony of cracks. “I always have the worst time trying to find a title,” Rena exclaims, but she says the company helped source this one. “The 1st or 2nd day of rehearsal, everyone was cracking joints and muscles. I said ‘That’s it!’ I wanted to make a sound score of everyone cracking bones and joints. But it was too complicated,” and her composer, Darryl J. Hoffman, said it wasn’t not going to work.

So the work has evolved into an invitation to see the seven dancers in one entity, in groups of 2 and 3 and “find the negative space in between them,” she says. Negative space (like the rests in music) is the space around and between bodies or beings or even framed within them as in the diamond shape made of legs or arms at several moments.

“Hold the frame in that way,” Rena says. “How do we frame each other? what are the spaces in between? where are the cracks and how do they lead us into understanding of ourselves and each other, and the space in between?”

And the motion continues, the group dispersing and coalescing with another fertile image Rena and the dancers use in this piece: as the group is moving together like a cloud, out of the mass a pillar of fog rises up that thickens into one human figure.

The demanding solos that ensue, one for each, are wonderfully evocative of the 7 Whim W’Him dancers’ very different characters, personalities, their vulnerabilities, quirks and very particular ways of moving, individually or as a single complex entity.

Photography Credit: All Whim W’Him images by Stefano Altamura