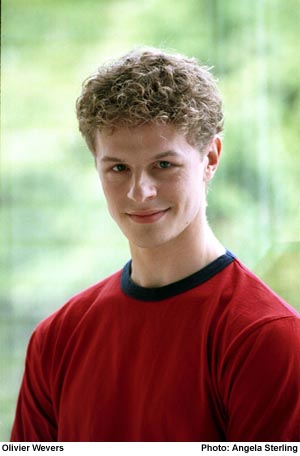

“It chose me, I didn’t choose it,” says Whim W’Him artistic director Olivier Wevers,

in answer to a question about how he came to make a life in dance.

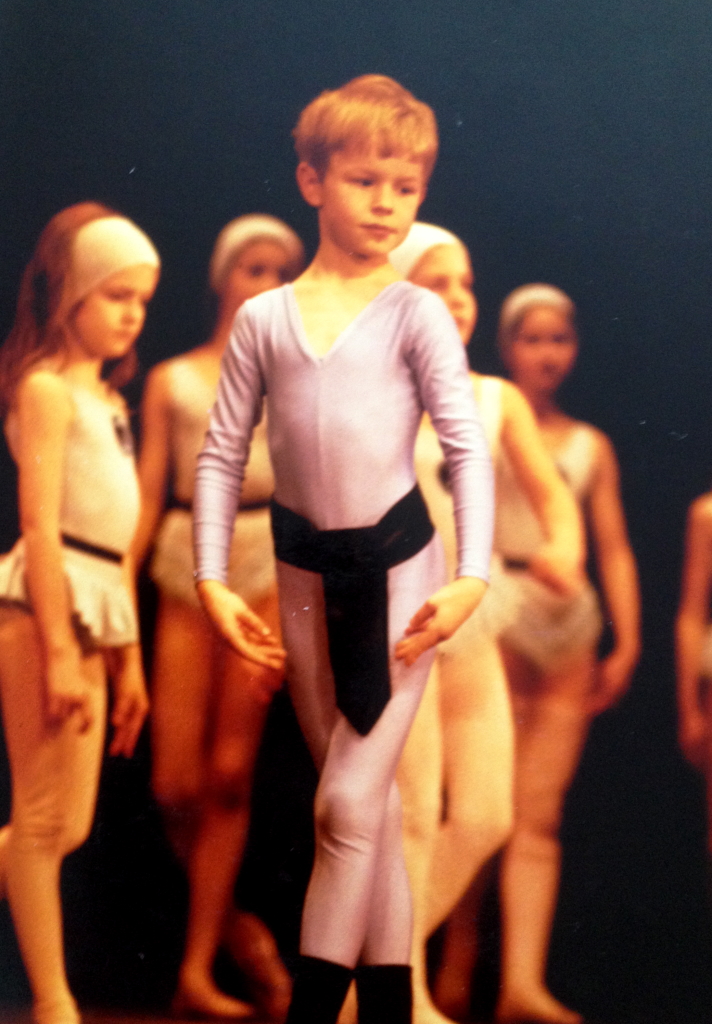

Olivier grew up in Brussels, Belgium. At the age of 6, he saw a ballet on TV and told his parents he wanted to be a dancer. He doesn’t know the details of how a ballet school was found, but he does remember his first class. He was the only boy. Dressed in the long red wool tights he used for skiing, he cried throughout. The teacher sat him up on the piano, and he watched from there. When his parents returned to fetch him,

they were told that he could come back again, but only if there was no more crying.

He did and there wasn’t.

I asked Olivier if he could say what appealed to him about dancing back then. He replied that he can say plenty of things about it now, but isn’t sure what drew him to it originally. He does remember being told that, even as a small baby, whenever music played he wanted to be picked up and danced around, by his grandfather or mother or any other grownup. But beyond that isn’t clear. When I proposed that maybe it’s similar to a taste—like chocolate, you either love it or you don’t—Olivier agreed.

With hindsight, other elements can be recognized as well. Despite his warmth and humor, Olivier even now comes across as somewhat emotionally reserved. In childhood, he was very shy and self-effacing, always avoiding dramatic situations, assuming a role of peace-keeper, negotiator. He preferred to remain in the background, calming things down. To this day he says, “Violence emotionally hurts me.” Dancing was something he could do, his own activity which let him to come into his own. And like many shy people, he found it easier to inhabit someone else or become a different character in front of other people, rather than to reveal himself directly. Dance became a medium for experiencing and expressing emotion.

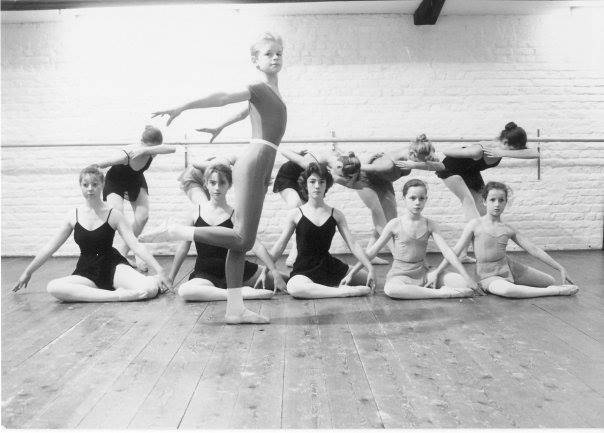

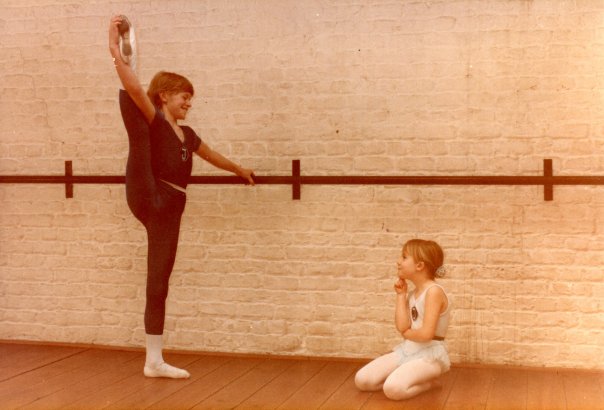

But after 8 years of dancing, by now at the top of the small private school where had trained, Olivier wasn’t really enjoying himself anymore or being pushed to learn new skills. His mother noticed and found him another school, that of former Béjart dancer Nicole Karys. There, all sorts of horizons opened up, particularly partnering, which would lie at the core of his dancing and still remains the heart of his choreography.

At 14, Olivier was, as he says, “short and small and weak.” Partnering class, with all the girls bigger than himself, was a real struggle. “My teacher made me do it. I had to do push-ups. It was scary and challenging.” But although he wasn’t good at lifting weights, it turned out he could lift girls. For a young male dance student, it is not nearly so much a matter of learning to heft a certain weight as sensing how another person moves and learning how best to work together with her. The best partners have a natural, instinctive rapport—“the outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace,” one might say.

Years ago, before ever meeting Olivier in person, both my husband and I were struck by the way he really looked at his partner as they danced, projecting the sense of being fully, totally dedicated to her. “To me,” he says, “looking is acting out emotion, making a human connection.” Partnering, according to Olivier, involves legs even more than arms, lots of awareness of not just one’s own body but the other person’s, and most of all a sense of balancing each other. In his own choreography, he always encourages his couples to “use each other.”

But underlying everything, there has to be solid technique. And that, in Olivier’s words, “was always a challenge until the end of my dancing career. The artistic part came easy. The artist wanted to just dance and move. I felt much more secure in acting. Technique was never natural.” As a kid, he had to cope with a “gumby body” and the physical weakness brought on by growing “about a foot” between the ages of 15 and 16. Everything ached, and he was always icing some body part or other. In the face of such rapid change, control was crucial. Instead of flinging his legs up in immense grand battements, he had to discipline his body. And in building strength, inevitably a certain degree of flexibility was lost. ’Twas ever thus.

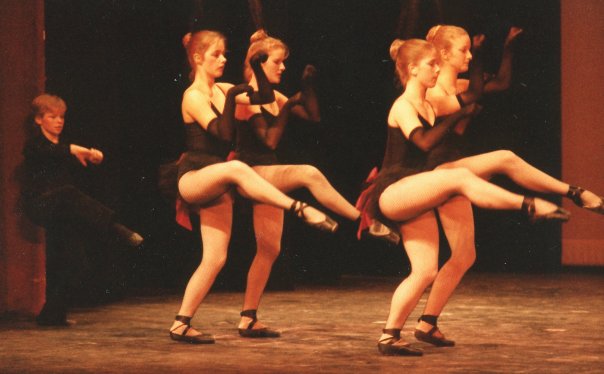

Five years into his training at the Karys school, Olivier started also taking professional classes at the National Theatre, where he was thrilled to see in the dressing rooms the lockers of Mark Morris and Baryshnikov. Nicole Karys, his teacher, got him in backstage and he was able to watch Béjart working and view performances sitting on the stairs. He also started getting some “random” jobs, such as a Volvo commercial and dancing in a production of West Side Story. But he wasn’t doing well at the Lycée and was restive.

It was at this point that he made the radical decision to leave Belgium for America.

Next time: Olivier goes to the US and Canada…

Photo credit: Rita Wevers