Rehearsal takes place facing sideways in the studio, not toward the mirror.

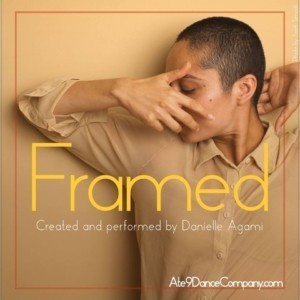

The choreographer is Danielle Agami. Her intensity is embodied in her small stature, compact body, concentrated presence, deep (in both senses) brown eyes, close-cropped black hair, and soft voice. Her serious demeanor is so strong that when she laughs or something pleases her, it’s a bit of a surprise to see her light up from within. Danielle is a compelling combination of quiet fierceness and friendliness, passion and playfulness—the latter revealed by her joy in the company of her lovely dog George, found on a roof in Israel as a puppy and her boon companion ever since.

Danielle Agami’s life has been as compact and articulated as her art. Although she’s only 33 now, the list of her accomplishments is long. When I asked “What made you dance?” she replied, “The truth is my mom says I pointed at the TV when I was very little and said ‘I want to do that.’ I forced my parents to let me.” In her young adult years, she performed in Jerusalem’s Hora Dance Company and attended the high school of The Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance where, from the age of 12, she also began to explore choreographing. The high school offered one opportunity a year for students to produce a new piece, which might get used by a local company, as one of hers was when she was 16. She studied ballet from age 5 through her high school, where the students also were exposed to Graham and Kylian and other choreography. For the most part, “We were informed with European voices,” says Danielle, ballet including “Russian influences from the 90s, wonderful teachers—not so much American choreographers like Cunningham and Limón.” Every year as part of the high school curriculum the students also saw Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company and Batsheva Dance Company perform.

She continues her story: “Then, at 18 we thought I would stop dance and go on to further schooling. But Batsheva offered me a contract. Batsheva was so respected and celebrated. I became a professional at 17. My parents were proud. It was organic, how it happened.” She adds, “And I allowed it to be and take over my life. No university. Nothing else. It keeps me busy and interested since I’m 4.”

Danielle’s life has not slowed down since. For 8 years, she danced first with the Batsheva Ensemble and Batsheva Dance Company under the artistic directorship of Ohad Naharin and choreographed as well. During part of that time, Danielle was artistic director of Batsheva Dancers Create and also served as the company’s rehearsal director, after which she went to New York as senior manager of Gaga U.S.A. (see below). A couple of years after, Danielle relocated to Seattle to found her own group Ate9 Dance Company, which later moved to Los Angeles where it thrives today.

By the time Ate9 came into being Danielle had already had a good deal of experience not only with theatrical production but with the many administrative aspects of running a company. (“The name Ate9,” she notes, “came from a joke I heard in 2012: Do you know why 6 is afraid of seven? because 7 ate 9. Somehow having a joke as the foundation of a crazy ambitious journey felt right to me.”) As an LA Times feature on Danielle commented, “Since arriving in town, Agami has become choreography’s It girl.” Her choreography has won a number of prizes, she was Dance Magazine’s Top 25 to watch in 2015, and in 2016 received the Princess Grace Award for Choreography. Up in the Pacific Northwest to create her new piece for Whim W’Him’s TRANSFIGURATE (June 08 – June 16, 2018 8:00 PM at Cornish Playhouse), she also performed her solo work, “Framed” in Portland.

The first rehearsal of the Whim W’Him piece that I watched, on a Monday, wasn’t going very well. Danielle’s approach was still unfamiliar because it depends on a very specific technique and hard for her to get across outside of that context. It was the start of the second week of rehearsals, and the dancers had already learned a series of movements, but there was some sort of yawning gap in communication.

By the time I observed again, that Friday, Danielle’s intensity was still there, but her radiant smile kept breaking out. things had turned around.

What made the difference? On the intervening days, she taught the company class/warm-up herself using the Gaga technique or movement language, developed by Ohad Naharin, employed with both professional dancers and non-dancers, and the basis of her own company’s work. Gaga, according to its website, “is a new way of gaining knowledge and self-awareness through your body. Gaga provides a framework for discovering and strengthening your body and adding flexibility, stamina, and agility while lightening the senses and imagination. Gaga raises awareness of physical weaknesses, awakens numb areas, exposes physical fixations, and offers ways for their elimination. The work improves instinctive movement and connects conscious and unconscious movement, and it allows for an experience of freedom and pleasure in a simple way, in a pleasant space, in comfortable clothes, accompanied by music, each person with himself and others.”

From the Gaga | people.dancers website

Or in the words of Ohad Naharin (in various places), “There are many things in it: the importance of yielding and collapse, of delicacy, connecting effort to pleasure, working without mirrors, learning to listen to your body before telling it what to do”; “We change our movement habits by finding new ones, we can be calm and alert at once. We become available”; and “We are aware of people in the room and we realize that we are not in the center of it all. We become more aware of our form since we never look at ourselves in a mirror; there are no mirrors. We connect to the sense of the endlessness of possibilities. …”

Danielle herself says of Gaga, “Its essence is endless creativity and discussion with our own bodies. I was introduced to it just when it was revealed to Ohad and the world. I honestly think it changed the history of dance. Technique is wonderful, but we need to know why and how, to be passionate and flexible, wise and mature.” Introducing this methodology to the Whim W’Him dancers “gave them more context and tools and gave me more tools to approach them.”

The music Danielle has in mind for the Whim W’Him piece is by Omid Walizadeh, an Iranian-born, LA hip hop d.j. In a 2003 interview, Walizadeh talked about his music-making process: “90% of my music is sample based, but I tweek and rearrange and change the samples to my bidding. Just taking a note here and a drum hit there and creating a whole different arrangement.” She says of his work: “He has interesting beats, a weird mix. Groovy but also abstract. Lots of detail and lots of background.” Like her piece too, which divides things up in novel ways. Often lighting or changes in music differentiate segments of a dance. In Duck Sitting, such divisions will be marked by particular moments of motion or stillness on the part of the dancers themselves.

Her new piece for Whim W’Him is called Duck Sitting. Its title, like that of her company, is another example of Danielle’s quirky humor. “Sitting Ducks is the source for Duck Sitting. Recently I feel as if humans are a mix of those two situations.” The choreographer is not fond of program notes, preferring to have the audience take from the dance directly whatever they can or will. So we won’t have the hints that a synopsis or verbal suggestions of theme might give. We, as the audience (and perhaps the dancers as well?), need to discover what we understand in the pure language of dance.

Photo credit: All black and white images by Bamberg Fine Art Photography