When you ask James Gregg where he’s based these days, Montreal or Los Angeles, he says, “That’s a good question.” He pauses before deciding, “LA I guess,” though he still has a base up north and has just been touring in Europe (Lithuania and Belgium) as a dancer with Montreal’s Rubberband Dance group, before taking up temporary residence in Seattle to make a piece funded by the Princess Grace Foundation to be created for Whim W’Him. It’s the first time a choreographer who has won the award is setting a piece on a company of a former recipient, namely Whim W’Him’s founder and artistic director Olivier Wevers.

As a child in Oklahoma, James began to dance because “It was in me.” Before starting classes at 9 he had done gymnastics. “But I got excited when I heard music” and saw people moving to it. So being, as he says, “an energetic kid,” he took ballet and jazz first, adding in hip-hop later on. “I always loved choreography as a kid and made dances, and my family watched.”

He trained with Ballet Oklahoma, Cece Farha‘s Range of Motion, Houston Ballet, Bolshoi Ballet Academy, Lou Conte Dance Studio and The Edge Performing Arts Center. While in high school he taught at a dance school and “had to choreograph there too,” though it does’t sound as if it was much of a hardship for him. After high school, at the age of 17, he had an idea of being a commercial dancer in LA, but joined River North Dance Chicago instead. River North was a bridge for him to the contemporary world. The company performed works of multiple choreographers and in various styles—modern, jazz, Spanish—inspiring James, who says his favorite thing became, and still is, “being in the choreographic process, as a dancer or choreogapher.” In Chicago he also made dances for smaller companies or on friends, scratching his “itch to create.” At 21 he got to choreograph his first piece for the company. In that hub of contemporary dance, he realized “That’s what I was meant to be doing, lighting a fire under my ass.” He educated himself in the possibilities of dance by going to performances, by reading and looking at dance in the public library, and by trying ideas and movement out on himself.

In 2005, he left Chicago for Canada, to dance with Les Ballet Jazz de Montreal and later Rubber Band and other groups. In 2011 his piece Radio Kids won the International Choreographic Competition at Festival des Arts de Saint-Sauveur, and he’s also choreographed for Milwaukee Ballet, Ballet Austin, Joshua Peugh’s Dark Circles Dance Company, Ballet X, Danceworks Chicago, and Springboard Danse Project Montreal, among others, and has been the resident choreographer for L’Ecole Superieure de Danse de Quebec as well.

The way James got connected with Whim W’Him was by sending in an entry after the first Shindig competition last year (where the Whim dancers pick the 3 choreographers—the second Shindig show will be this coming September). But since he had worked at Northwest Dance Project in Portland, Oregon (like Loni Landon another choreographer who had done a piece for Whim W’him and is a close friend of his), he was already attuned to the Pacific Northwest. “And after five minutes in a Starbuck’s with Olivier,” James recalls, Olivier asked him to create a piece on Whim W’Him, in a separate non-Shindig program. Of James’s work, Olivier says, “It is physical without playing at extremes, connected without being predictable, and surprising in the way bodies are articulated.”

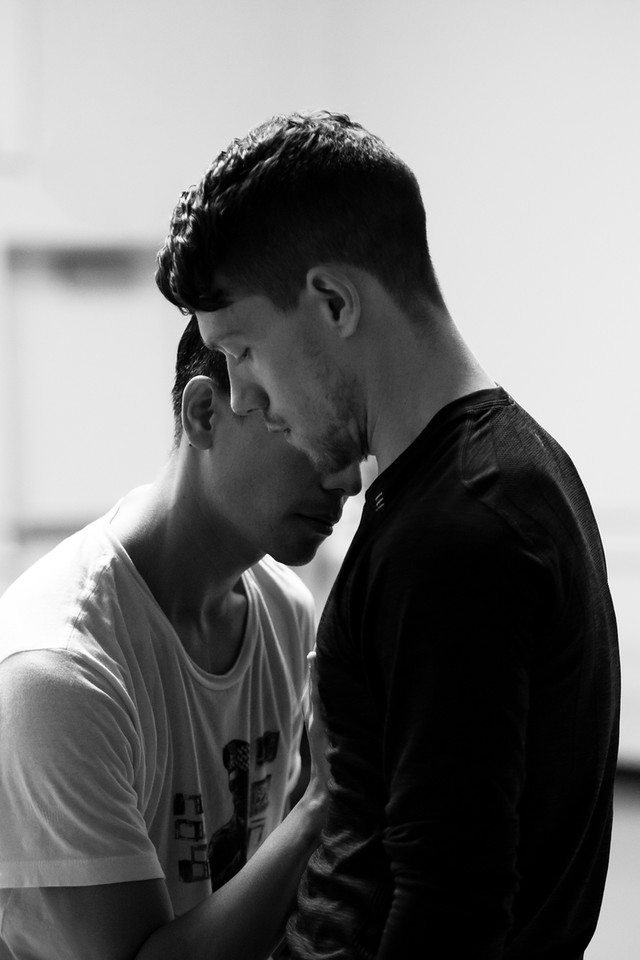

As to the theme of his current creation, Into You I Go Willingly, James says that his last 3 pieces have been “delving into my own past life and relationships, my connection to the audience and to the men in my life.” This particular work, a tense and tender duet for Jim Kent and Patrick Kilbane, is “about a close relationship—getting to know someone, when you both have your guard up.”

“Each piece is different, of course,” says James, but for this one he tried ideas and movements out on himself and on the first day brought into the studio 3 or 4 sequences to teach the dancers, “and we went on from there.”

“It’s nice,” James reflects, “to see two men dancing together, in physical and emotional terms, but not in your face— talking it out.”