“I love a good challenge,” says Banning Bouldin whose Limitation Etudes 7-10 premieres this Friday, September 8, as part of Whim W’Him‘s CHOREOGRAPHIC SHINDIG III at the Erickson Theatre off Broadway on Seattle’s Capitol Hill. “It’s in my personality to seek them out.”

Seeking out challenges, appreciating what they can teach her, and incorporating their lessons into her creative life seem to be what make Banning tick. From going along as a shy, clingy child to try dance class, to recent life-changing health trials, Banning takes on new circumstances with wide-eyed curiosity and humor.

“My mom had no idea how it would take,” she says of her reaction to that dance studio at age 5. At 9, Banning auditioned for Nashville Ballet‘s Nutcracker. “I fell in love all over again, this time with the rigor and theater.” She danced with Nashville in the corps de ballet as a teenager, but got no modern dance training at all. As John Pitcher writes in nashvillescene.com, “A decade ago, anyone in Nashville who wanted to study contemporary dance had just one option: leave town. The city, for all its progress in the other arts, remained a modern dance Mojave, an arid landscape that provided few opportunities to young dancers who wanted to follow in the footsteps of Merce Cunningham, Trisha Brown and Alvin Ailey.” When Banning read in Dance Magazine about Juilliard‘s first ever summer dance intensive in 1996, she was drawn to the bright colors and partnering depicted. “Oh,” she said to herself, “ballet dancers can do modern dance.” She thought, “Well, I won’t get in,” but sent a video anyway. And at the audition, then director of the Dance Division Benjamin Harkarvy took her aside to ask how she would feel about early admission.

Of her move to New York at the tender age of 17, Banning says, “I’m glad my mother experienced a moment of madness. I never felt I fit in in Nashville growing up there.” It’s true that she “loved the rigorous process of doing—not watching—ballet, and loved Giselle’s mad scene,” but classical ballet was not really her kind of dance. The first year at Juilliard was “really tough. There was huge pressure. I went to school from 9 till 9 and studied composition from 9 to midnight. Adapting to that rigor was a major shift.” She adds, “Once I got it, though, it was great.”

Her next big shift was from the academic, scholarly environment of Juilliard, on New York’s upper West Side, to the scrappy, gritty atmosphere of Chicago cafeterias and school auditoriums. Joining Hubbard Street 2 after graduation “taught me the value of connection with communities,” she says, “and of different scales and environments.” But Banning, who hadn’t gotten New York out of her system, went back there to free-lance with 3 companies and to struggle with the financial and artistic challenges of knowing neither where the next gig or the next meal would come from.

Though clearly Banning figured out how to survive in the fiercely competitive world of New York dance, it’s hardly surprising that Europe would attracted her. “There’s a certain amount of romance about European artistic life,” she says. Learning to live in another country always takes some doing, but at the Cullberg Ballet in Stockholm, she worked with “some of the best dancers I’ve ever seen or met.” She also went from the loner’s life of juggling multiple jobs to the stability of a 52-week contract and touring with a company that handled everything. It seemed a kind of ideal. Yet “Ironically, I kind of missed making my own schedule,” she says. In Sweden the dancers were in essence told: “These are the days for seeing your family or lovers.”

Banning felt a strong need for more connection, which is why she went next to France, where, according to her company website, “she began to develop and teach her own syllabus in Paris at the Théâtre de la Danse and Studio Harmonic. That same year she joined Rumpus Room Dance, based both in Portland, Oregon and Goteborg, Sweden.”

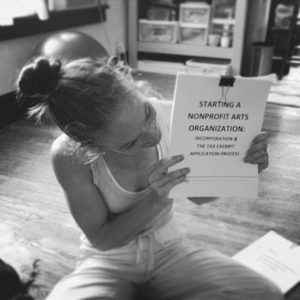

Ultimately, it was the desire for more time—with family and her partner, for gardening and for being part of a community she knew and loved—that sent her back to Nashville in 2010. With enough commitment and energy for 3 regular people, she taught contemporary dance on her own, at Vanderbilt University and for Nashville Ballet, and within a couple of years and with no administrative experience she founded Nashville’s first contemporary dance company. Greatly influence at Juilliard by Benjamin Harkarvy, who approached dance “as an international language with many dialects,” she called her new venture New Dialect.

A small company of dancers, as well as a collective, New Dialect is dedicated to advancing “the evolution of our art form by inspiring people of all social backgrounds, cultures, and generations with authentic, high-quality dance workshops and performances that connect us more deeply to ourselves and each other.”

The most recent challenge of Banning’s adventurous life has been a harsh and somber one. Last November, Banning’s body seemed to revolt. All of sudden her legs didn’t work, and she was incredibly weak. Tests, including a spinal tap and multiple MRIs, were performed, and she was eventually told that an autoimmune disease was attacking her spinal cord and that it might continue to happen. Here were challenges unlike anything she had ever encountered, “physical limitations I had never known. I could recover soon or never—have a comeback or face paralysis and blindness.”

“It is only in the last couple of months that I can move my body well,” she notes. Banning still has a lot of numbness and tingling in her lower body. She continues to combine neurological physical therapy, acupuncture, the Feldenkrais Method, and the Bowen Technique to aid in her recovery, but the outcome is still unknown.

The process of not ignoring but exploring the forms and implications of limitation helps not only to keep her sane and focused and to bring her back toward physical health, but is the source of a new path to creating dance for her.

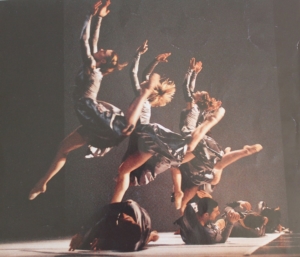

The result is an ongoing series of Limitation Etudes, of which the present Whim W’Him piece is the latest iteration. For Banning, strength has come through interrogating “physical limitation and developing capacities I wouldn’t have had otherwise.” Pictures—of elastic straps binding and of trying to move through water—kept coming into her mind. But “I had to experiment with choreographing without physical illustration.” The 1st 6 Etudes were developed with Banning’s company in Nashville and Steamboat Springs, CO. Limitation Etudes 7-10 are being aired by Whim W’Him in Seattle this weekend and next.

“In the first minute of the first day with the ‘Whimmers,'” Banning saw that the dancers were “so open and willing. From the Etudes I had already done, I knew what I wanted to explore.” Under her guidance, dancers sat on the floor and wrote about limitations, real or imagined, that they had encountered and “that we all experience.” In words and then while moving, they probed the meaning of ‘frailty,’ ‘inhibition,’ ‘failure,’ ‘defects,’ ‘spatial limitations.’ “Dancers are artists and athletes, specimens in front of a mirror looking for flaws, until they almost become caricatures,” Banning says. Four movements expand on these themes.

7. Perseverance

8. Monologues on the theme of Mastery

9. Resistance

10. A Partnership on the theme of Assistance

The music is eclectic. Electronic and piano by German pianist and post-modern composer Nils Frahm that “put me in mind of an odyssey”; solo piano by Joep Beving; and music by Israeli composer Sagat. “I like a lot of topographical range,” Banning notes. “I like to sample music from different composers to reflect different moods and landscapes in an overarching landscape.”

Watching Limitation Etudes 7-10 in rehearsal is to realize this is no mere thought experiment or tidy exercise in empathy. It is real pain and personally experienced emotion translated into dance.

Photo Credit: First and last 7 images by Bamberg Fine Art Photography, all others courtesy of Banning Bouldin