Tomorrow, September 18, 2021, dancer Jim Kent will perform for the last time in the theater with Whim W’Him,* the company he helped from its inception to shape.* At the very start, just before for the opening program in January 2010, my first post on him began:

Jim is an independent dancer and an independent man. He dances for several companies, but doesn’t invent or conceive of himself inside of any one institutional structure. In his life, both precarious and free, he thinks about balance, not just in his dancing, but between the various aspects of his life: dance—modern, but with a good deal of training in ballet; music—principally piano, also violin; and the supplementary work needed to bring in enough money to live, as a waiter, a piano player for ballet classes and various other jobs.

“It was always necessary to balance for income,” Jim recalls now. Of his work in restaurants, he says he thought of them as more than a means to an end. There was the creative aspect and the food, its presentation, the offering of it. He was a waiter at James Beard award-winning chef Matt Dillon’s Sitka & Spruce for its whole 8-9 years until it closed, and others since. For years he played piano to accompany classes at Velocity Dance Center, Pacific Northwest Ballet and Dance Fremont. And he continued to freelance occasionally too for Dayna Hansen, Mark Haim and St Genet among others. “But I always had to gauge if I could work around Whim W’Him.”

There was an interesting transition period, “shifting from freelance to ‘contemporary dancer’ with Whim. A new term to me—I definitely didn’t know at the beginning if there would be a real contract ever,” says Jim, where the dancers have a fixed number of weeks salary, benefits, and regular rehearsals. “It became family over the years. I’m not sure I expected a full-on company experience, though. Family and a contract! That meant more hours and more days to devote to craft and deeper and richer relationships with choreographers and the material.”

Another excerpt that original post on him: Of working with Olivier for the first time. Jim said, “I don’t want to sound like it was just easy and I picked it up like nothing. It was definitely new and foreign. I enjoy that part of learning new things. It’s different, it’s challenging. And there’s the draw.” [I added,] in a group, Jim can be reticent—seeming quite serious, restrained, even shy. In younger years it might have bothered him, being in a way, the odd man out. But on the rehearsal floor he leads off with assurance and pizazz, and can project a quirky off-beat sensibility or terrific earnest, deadpan humor…

In person, off stage, Jim is still modest, calm even serene, and rather enigmatic, although he is quite open in talking about his life, ideas and feelings and retains a lovely wry sense of humor. As time has gone one, his craft has developed, his understanding deepened and he has been a defining presence at the core of Whim W’Him. In conversation this week, I mentioned ‘sickle pickle’—the deliberately turned in foot—and other distinctly Whim-ish steps or positions, that de-emphasized classical training or even explicitly contradicted it.

“A vernacular is necessary,” Jim remarked. Even if a movement had a simple balletic name [ronde de jambe, battement, arabesque], Olivier always wanted to redefine it, so it could be thought of without that baggage. “It’s living history, a name and the aesthetic being formed in the process of creating a specific style,” Jim says and also noted that he had never thought about codifying or teaching all this, until Karl Watson came along. With Karl’s joining the company, “He has helped to make it organic, by taking the reins of making the company’s identity so explicit.”

Jim says, “I trusted Olivier’s vision always, even when I didn’t necessarily know what it was.” New choreographers brought challenges, “with new ‘bosses’ every couple of weeks. Some I didn’t know at all or not much about their aesthetic and ways for working—whether they would take time to develop [ideas], or if they worked really fast and were very inspired immediately so you sort of had to hang on their every word.”

One favorite part of the process for Jim has always been day 1 or 2. “There’s electricity in the air. We’re all in the same boat. There’s not much casting yet. It’s a even playing field. A feeling of freshness and possibility in the air.” But over time he gained confidence to be himself and offer his own ideas. “It was like playing in different people’s sandboxes. Their sandbox and their rules. You have to play by other’s rules. Most choreographers, though, give you a lot of agency to contribute.”

When I ask about favorite pieces or choreographers, he demurs, “except Olivier, of course. I learned to genuinely enjoy his interest in partnering. I used to hate partnering. It made me want to jump out the window. Now it’s one of my favorite parts—the connection, giving and receiving. I’m totally surprised by it. Olivier has specific ways of partnering, There is something about his partnering—about when he decides to hide or show something, to create magic for the audience.”

This is a really interesting bit. Both because Jim disliked partnering in the beginning and becauseof all the tricks Olivier employed, though Jim doesn’t want to call them that—rather the various ways Olivier devises to influence what the audience perceives. Sometimes the effort of it is part of the point; sometimes the hardest things are meant not to be taken as difficult but seen simply as magical.

Jim says Olivier “is really generous in sharing. Even more than you want sometimes. He wants to iron out and bad habits or knowledge. There’s rawness. [Like a first draft I was thinking, where what you want is right there and needs to be preserved precisely, even though it’s still rough and will be developed and changed. “It’s a high bar,” Jim adds. “Olivier knows he’s going to render it out even further, endlessly. This is kind of the beauty of performance. There is so much information to be absorbed by a dancer, wanting to understand where the choreographer is coming from.”

After quietly storing it away through many works, Jim says, dancers can bring out the compiled information and use it in new work. ‘It’s empowering to work with so many people—about 40 in his WW career—and to be in a new process and [know how much] I learned.’

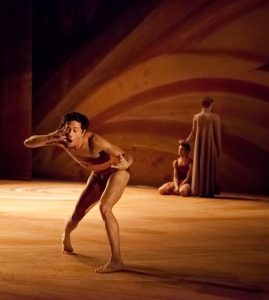

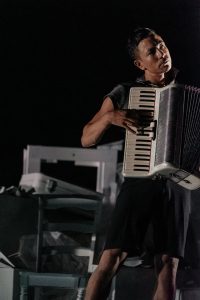

In the multitude of pieces in which he has danced over his 12 Whim W’Him seasons, Jim has been pursued, adored, manipulated, lifted precariously overhead. In a 2015 post, I wrote that he “stood in as a representative of humanity in [early] Olivier works such as 3Seasons and Crave, and danced the one whose fate is followed in Alone Is the Devil,” inspired by the idea of the 7 deadly sins. During the next half dozen years, Jim explored a great variety of roles, as part of the ensemble and individually, including that of The Little Prince himself in Olivier’s evening length This is not The Little Prince (first onstage in June 2019, then in last year’s film version)—and added accordion playing to his instrumental accomplishments.

“Whim has been the place where I’ve grown up as a dancer and really learned to dance. It taught me how I do—and don’t—like and want to move. I learned so much more than I would have in a company with a monoculture.”

The other day, he said, “It’s just Whidbey now and then I will be at the end of my Whim W’Him contract. It’s been a constant for 12 years for me and for the company. I haven’t really cried yet, I don’t know if it will hit till later. But last weekend at Vashon, there was lots of closure. There was a big toast in the green room after, and also a whiteboard where anyone could write messages. It was a beautiful, sweet weekend. Shared memories.”

Jim Kent has been a defining presence; his absence will be keenly felt. But his imprint will remain on the unique and versatile style Whim W’Him has created and in the close-knit community the company has formed.

*This final performance of the fall program will take place at 7:30 pm at the Whidbey Island Center for the Arts. (Live performances are subject to COVID-19 reopening guidelines and public health and safety mandates.)

Filmed versions of the program, by videographer Quinn Wharton, debut on September 23.

Photos by Bamberg Fine Art Photography (Kim & Adam Bamberg and Molly Magee) and Stefano Altamura