“It’s amazing! Six hours all together in the studio, big space, big movements, in socks. It almost felt like a normal day,” said Olivier Wevers, Whim W’Him’s artistic director and the choreographer of This Is Not The Little Prince.

It’s a modified normal, to be sure, since for the first two weeks dancers still had to keep their distance, wearing masks and not touching. At the end of that period, after testing, it was into a strict pod with weekly testing, strict guidelines and no outside contacts (as for the two films of the Choreographic Shindig program in September), until the completion of filming on Dec. 19. But early on, although they could dance in the same studio with Olivier and eat lunch and chat as in the old days, they had to do it spread all across the large room.

Work was limited to solos or group-but-not-intertwined sections, of which, as Olivier points out, there aren’t that many. This Is Not The Little Prince in particular is mostly made up of the intimate duets and trios, that he loves to choreograph. At the end of that first day, Olivier said he was very tired. He hadn’t really danced for a long time, as the two films that premiered last month were choreographed by others, and gym workouts have been out of bounds. There’s a limit to how in shape one can keep in the confines of a small apartment, even with long walks outside.

Ashley, left; Michael, middle kneeling; Andrew, middle standing during the filming of ELSEWHERE by Mike Tyus & Madison Olandt

Since the original production of TINTLP, three of the dancers are new to the process and the piece, Ashley Green, Michael Arellano and Andrew McShea. On the first day, the dancers and Olivier (no one else for safety reasons) sat on the floor, talking and planning, discussing ideas, “so we are all on the same page.” And, of course, the transformation from live stage performance to film requires not just minor adjustments, or even simple word-for-word translation, as it were, but a total re-creation for the screen with the collaboration of New York filmmaker Quinn Wharton. The original music of composer, multi-instrumentalist and conductor Brian Lawlor will be reconfigured by Brian as needed to enhance the new format.

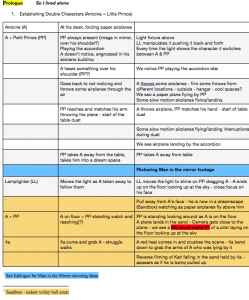

I’ve been watching a straightforward archival video of the first incarnation of the piece, alongside a blow-by-blow worksheet of the whole new version, created by Olivier in three columns. Notes on characters in the first. Actions in the second. Camera notes in the third:

TINTLP’s basic dual approach—combining the story of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s classic, The Little Prince (a picture book not necessarily for kids), with exploration of connections between the life of pilot/author Antoine de Saint Exupéry and the book’s narrator—still remains at the center of the film.

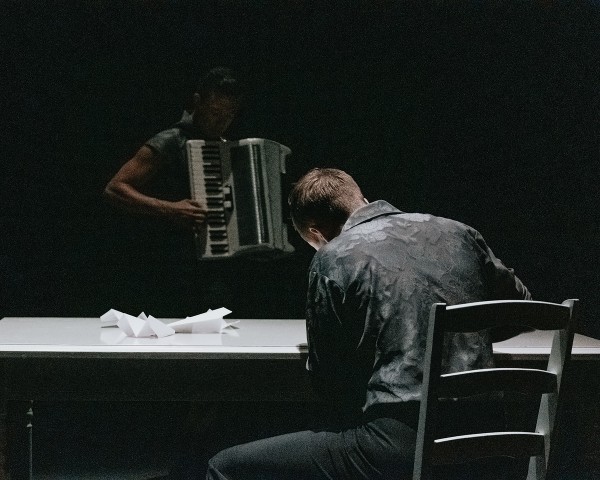

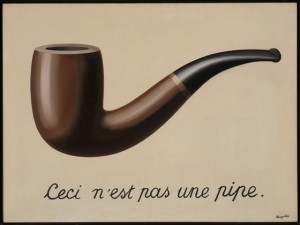

The Prologue opens, as it did in the original 2019 stage version of TINTLP, with Antoine (danced in both productions by Karl Watson) engrossed in folding paper airplanes and the Little Prince (Jim Kent, both times) playing a haunting melody on the accordion just beyond the spotlight. But soon the limitations of the stage are sloughed off, and the wider world—visual, historical, fictional—comes rushing in. Not, though, by any sudden conversion to naturalism. While the film expands beyond the limits of a small theater on a modest budget, the Surrealist slant of the enterprise is kept intact. Since his first acquaintance with René Magritte as a young teenager in Brussels, Olivier has been drawn to the open-ended mystery of Surrealist painting, its metaphors, poetry and puzzles. It is a fitting lens through which to see Saint-Exupéry and The Little Prince, whose riddles and layers of meaning are a large part of the book’s universal and enduring appeal.

Magritte’s famous painting ‘This is not a pipe’ (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) calls attention to the fact that no artistic rendering—however precisely detailed and ‘realistic’—is real. It is always only a rendition, an interpretation of the subject through the mind of the painter, and the beholder. In the same spirit, This Is Not The Little Prince does not attempt to translate The Little Prince word-for-word in dance, but rather to tell a human story of self-discovery by delving into the rich understory of influences and connections in the life and mind of Antoine Saint-Exupéry that led to the writing of his most famous book.

The Surreal sensibility of the film will be heightened by the miniature art of Talia Silveri Wright, who describes herself as fascinated by dimension, scale and ephemera, all preoccupations that should dovetail, to telling effect, with Olivier’s vision.

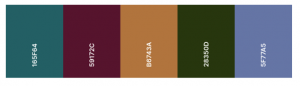

There is a specific color palate for TINTLP as well. In the stage production, the costumes of the snake and the fox, differed from those of the other characters by a faint trace of their associated color. In the film this idea will be taken further, as filters in these shades will help create a specific mood or character association in the lighting of scenes. The Prologue and Epilogue will have particular associated filters, and the coloration of the characters will be utilized in scenes to which they are central as well.

Moving collages of snapshots from the adventurous life of Antoine Saint Exupéry and his long and stormy relationship with his wife and principal (though far from only) love, Consuelo Suncín de Sandoval, comtesse de Saint Exupéry, will add texture to the film.

It’s another big new chapter in the ongoing adventure of keeping dance alive and connected to our time in the new world of coronavirus.