In these shifting, distanced, untethered times, we hunger for anchor points to hold on to. We crave juicy, thirst-quenching thoughts, feelings and ideas to engage with. But reality—the solid, the substantive, whatever actually exists—seems out of reach these days. Like images receding in a mirror or the shadows on the wall in Plato’s cave, real life seems always to be elsewhere, an infinite regress.

Elsewhere may not be better than where we are now, but because it is where everything is real and we will recognize it when we get there, it is where we want to be.

It’s our escape, and also the title of Mike Tyus & Madison Olandt’s new dance film for Whim W’Him, now viewable via mys.iqs.temporary.site‘s IN-WITH-WHIM platform as of Thursday, September 24, 2020.

As is traditional with The Choreographic Shindig, for its 6th round the dancers chose the choreographers. The duo of Mike & Madison, picked from over 140 entries, drove to Seattle from LA in order to make their new piece, while avoiding the possible Covid exposure of plane flight. (The other two Shindig VI choreographers, Ethan Colangelo and Mark Caserta, prevented this time from coming to Seattle by the pandemic, will have their opportunity next year.)

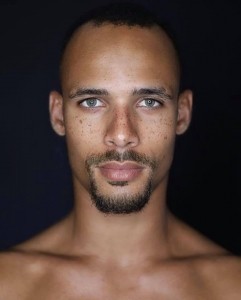

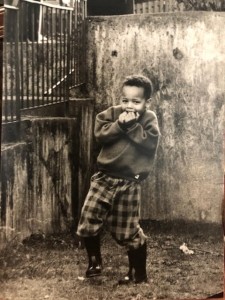

Both Mike & Madison have been movers from birth. But at age 11, Mike had to have major reconstructive leg surgery to correct bone misalignments caused by Blount’s disease. Afterwards, a physical therapist suggested dance to help with recuperation. Says Mike, “I immediately was hooked. I found what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.” Since then, “Dance has taken me all over the world. It’s a great way of meeting people, building relationships and community.” In 2004 he co-founded the dance group Urban Poets and toured the globe.

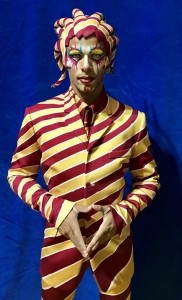

About 4 years later he moved on, to dance with Cirque de Soleil, collaborate with renowned composer Danny Elfman, and dance, teach and co-create for Pilobolus. In 2014 Mike became a founding member of Los Angeles based Jacob Jonas The Company, which seeks “to bring dance to a wider audience through collaboration, performance, media, and education.”

As one of five children whose mother was a dancer and father an actor, Madison grew up in Thousand Oaks, CA, surrounded by the performing arts. Since she loved leaping about, jumping off the couch even as a tiny child, she early began gymnastics classes, where “I found my body.” Madison came to be ranked among the top 20 for her age group in the country. She loved the movement and the skills she learned, but found herself increasingly ill-at-ease in a super-competitive environment. “The training-for-the-Olympics aspects of gymnastics didn’t thrill me.” She would choreograph in her room to music, and at the age of 14, she switched gears to dance. Enrolled in the local Cuizon Ballet Center and later at UCLA, she still won prizes while learning many styles—jazz, hip hop, acrobatics, Bharatanatyam, tai chi, Cambodian and West African—besides ballet and modern/contemporary dance. At the university she earned a double degree, in dance and psychology. It was there that she really became aware of “the intelligence of dance. Creating, not just mimicking, the freedom to explore what you want and can do.”

With Diavolo / Architecture in Motion, which she joined while still in college, Madison had her first exposure “to being in dance. It combined athletics and dance, travel, and both the commercial and concert world.” As noted on its website, “Diavolo blurs the lines between dance, acrobatics and parkour for one goosebumps-raising experience called ‘architecture in motion.’” Along the way, Madison has found unique ways to incorporate her many influences in her own dancing and choreography.

The story of how Madison and Mike started working together goes something like this: After he saw her dancing and asked, “WHO IS THAT GIRL?” fellow dancer Derion Loman, also from Diavolo, introduced them. Mike and Madison’s creative instincts meshed at once. He says, “It’s hard to find a partner who gets it immediately. I had Maddy in mind, and Derion too, for Out of Nowhere,” a piece he was creating for Jacob Jonas The Company. “The first time in the studio, it just went. I never created so much so fast.” The result was submitted to Whim W’Him’s Choreographic Shindig VI, for which Mike and Madison wanted to co-create an expanded and transformed collaborative work.

But then the virus changed things radically in the real world. Luckily, their friend, fellow dancer and now housemate Joy Isabella Brown, who was already skilled with a video camera, helped guide them into rethinking their ideas in terms of film. “She helped monumentally in bringing something live to film,” Mike says. Within the embrace of these fertile artistic connections, instead of being merely an exercise in frustration and curtailment, the pandemic managed, as Mike put it, “to open up the floodgates of possible physical dance and imagination.” When Madison and Mike drove up to Seattle to start rehearsal, Joy came too and a new piece has entirely emerged.

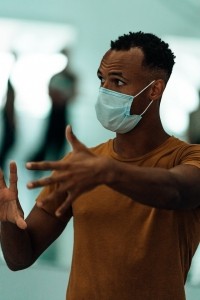

The 3 of them (masked) worked with the dancers (at first, masked also), to bring the 2 choreographer’s ideas to fruition and put them into a form that, by the time videographer Quinn Wharton arrived for the definitive filming, would be optimally suited for the highly quirky and inventive piece envisioned by all the collaborators.

Meanwhile the dancers, after careful quarantining and testing, moved in together into two pods or bubbles so they could dance together unencumbered by restrictions on touch or breath.

Yet due to the nature of the piece and contact limitations early on, in the whole first two sections, there is no touch, only dancers swooping in and out or moving in parallel.

And that is one of the curious things about Elsewhere—how the extremely layered nature of the film-making process echo the themes in the piece itself. In a “normal” Whim W’Him season, as with most any dance company, there are essentially 3 acts to each production. Studio work involves the dancers and the choreographer. At the theater, the additional magic of costumes, props, stage setting (if any) and lighting enter the picture to enhance and burnish the underlying movement of the dance. The third is performance before an audience.

In making a film, the audience is not there during live performance, and the other elements are broken down and re-combined quite differently. The first 2 scenes of Elsewhere were rehearsed and recorded in a basement space not normally used as a dance studio. In the early stages, the 7 dancers were joined by not just the 2 choreographers, but by their co-conspirator, Joy, filming with her camera. Mike too often took a shot at shooting footage. These efforts were overlaid and changed around again later with the much anticipated arrival of master cinematographer Quinn, of whom Madison says, “We were really excited to meet him. He’s a great listener with the tools and experience needed.”

In first scene of the actual film, the heads of the dancers are enveloped in long stretchy hood-like appendages that completely obscure their faces. It is sinister, touching and even funny at the same time.

The second scene, still in the white-painted basement, revolves around a strange little jury-rigged device, whose apparent old-fashioned simplicity masks modern tech complexities, in a home grown sort of way. This central prop was actually the shell of a very old white-painted TV, whose screen was the face of an iPad, stuffed into the box with wadded paper. A pre-recorded video, timed to match the movement of the dance, unreels moving images of dancer faces, often distorted (by pressing against a glass-topped coffee table—”We make us of what we’ve got”) or even underwater (where a segment was filmed in a borrowed swimming pool).

Often dancer faces do not coincide with the body dancing behind. Everything seems out of joint. The device itself is wielded by yet another director of sorts, dancer Karl Watson, who deploys it. The transparency of the dancers’ costumes mocks the opacity of the enigmatic images.

The wealth of involved parties produced fascinating moments where Quinn was filming the dance with his professional cameras, while Mike or Madison shadowed him closely to see what angles and moments he was capturing, and the others (including Whim W’Him artistic director Olivier Wevers) observed intently from the edges. Since all are dancers or former dancers, the scene itself became a larger dance inside of which the film was being recorded.

Madison and Mike say they both saw themselves as directors but, recognizing the other’s equal investment in the project settled on having each of them direct one of the first two scenes, with both of them directing the third where, in Madison’s words, “we learned how to collaborate on someone else’s vision.” Her words resonate even more when the videographer’s role in overall direction is factored in.

For somehow, the varied input of multiple contributors has coalesced into a subtle, wise and witty movie. Layer upon layer upon layer upon layer, until in the third and longest scene, the whole crazy conglomeration of fragmented individuals splits apart the proscenium, making a break for the outer world (a theme similar to that of Annabelle Lopez Ochoa‘s Grassville, though in a totally different style) and the damp and sandy togetherness of real touch. The ending, at once uplifting and sad, is a seeming commentary on both the capacity for transcendence and the limits of art. And, as in all 4 of these films produced in 2020 so far, in conception and execution, Elsewhere becomes an unexpected embodiment of Olivier’s collaborative dream in founding Whim W’Him.

Photography credits: Whim W’Him images by Stefano Altamura