Omar Román de Jesús doesn’t really remember a time when he didn’t dance. “Mostly I felt like doing it—it was natural.” So was creating dances. As a child he would try out steps and movements in front of the mirror. When, at 12, “I wanted to do it more seriously,” his mother noticed and looked into dance and my brother found a school for me.” The distance from their home in Bayamón, Puerto Rico, Escuela Especializada en Ballet Julian E. Blanco in San Juan was not so great, but it took about 1 1/2 hour each way in heavy traffic, and it was a very serious program. His mother would wake him at 5 am and he’d sleep in the car on the way. “It was rough,” he says of both his own schedule and his mother’s long stints at the wheel of the car.

At school, after 7:30 am ballet, there were other dance classes (in levels 1-6 as he progressed), including an elective such as a men’s class or Flamenco or jazz or modern, and academic studies too: Spanish, social studies, math, etc. Then the long ride home again.

At the performing arts school, “Only ballet was considered the real thing. All the rest felt wrong. If you end up in contemporary world, it’s because you’re incapable,” he recalls. “Even if I liked contemporary and jazz, I pushed myself in ballet.” After 5 years, Omar was accepted into the 2nd company of the Balleteatro Nacional de Puerto Rico and then into “the big company,” during which time he won the Championship Cup and Gold Medal at the National Dance Competition in Puerto Rico. The director of the company, Miguel Campaneria, saw a lot of potential in him and “took me under his wing,” giving Omar the opportunity to dance and see other cultures, including Japan and the US mainland. “I am very grateful,” he says. “It was the best thing ever.”

Up through this stage in his career, his training and everyone involved in it—directors, teachers, artists—had been “pretty much into ballet, ballet, ballet. Students are very influenced. If the authorities have rigid thinking, so do the students.” Omar’s career and his sense of what kind of a dancer he was reached a turning point when Puerto Rican choreographer Rodney Rivera came to set a contemporary work for the Balleteatro Nacional. It was a revelation. “I couldn’t deny it any more,” says Omar. “Technically, physically and organically, I felt alive and present on stage, in embodying a role and in the reactions of the audience.”

So what next? He decided to try for something in the US. New York City was “the place to go.” Omar auditioned for The Ailey School and was offered a scholarship. “It felt so weird at that moment for the ego,” he says, “a step down back into school.” His friends asked, “What are you doing??” But Omar knew: “I have to.” Turning in this new, unclassical direction. “There was still much more to learn and experience in dancing first” before becoming a professional.

It was harsh at the beginning, though, not knowing anyone and not knowing the language. “I almost gave up.” On the phone to his mother, Omar told her about his troubles. But after all the struggles to get him that far, she said, without hesitation, “You stay there for 6 months, then come home if you still want to.”

So he stayed on, learning more English from Netflix, starting to make friends. It helped a lot that Ailey students were drawn from many places and “were used to people who didn’t yet know how to fit in.” They included him, thought his attempts to express himself in English were “cute, and were very patient with me,” while his language skills improved from sentence fragments with lots of hand gestures to real fluency. Omar says he is very grateful for that. “It’s very important to have a place where you’re comfortable and can make mistakes. There is so much awkwardness you have to go through to get to comfort. They focused on success not what’s different.” And then: “Oh man, no coming back. All of a sudden there was a new set of goals and dreams and I had to find a path to that.”

Also at Ailey, just starting that year, “You could audition for an extension of the program, where you worked with 2 choreographers each semester. It was really motivating. Not just concentrating on technique, but imagery, space, negative space, things that you don’t get in class.” Through Kate Skarpetowska, one of the program’s choreographer, he learned about Parsons Dance, where he spent the 4 years after Ailey.

At Parsons, “I learned to stretch my limits,” says Omar. It didn’t happen right away, though. “Two years into Parsons, I felt I wasn’t fully invested. Friends were into their dance dreams already. Why were their lives so easy, mine so hard?” Until finally he realized, “I have to put myself in the present. I need to invest in this and focus. Find little pleasures.”

A transformative experience of his Parsons year was working with special needs children, through a company initiative of Autism-Friendly Programs, that feature “sensory-friendly workshops and relaxed performances for audiences of all abilities.” The piece Omar has choreographed of which he is most proud grew out of these experiences. Parsons Dance commissioned DANIEL for the company’s 2017 Joyce Theater season as part of its initiative to support emerging choreographers through the GenerationNow Fellowship. Its inspiration was a very difficult autistic boy, who might “punch someone in the face as an expression of love” and his heroic mother. “He was unmanageable for anyone else.”

The Joyce work didn’t start with this theme, but Omar “couldn’t help thinking about it, and all the elements and the music—6 very different pieces, R&B, classical, the spoken voice…” The whole creative process was, as it is so often, complex and mysterious, with multiple connections and nuances finally falling into place. So many questions needed answering, about how to structure the dance emotionally; how to relate to the dancers as both one of them and the choreographer , how to invite the audience into the kid’s mind, but “in an abstract way so that the audience gets to a place, yet without necessarily catching on to the specific situation.” He says, “The only literal moment in the piece was when the kid has a tantrum, danced by Eoghan Dillon, a magnificent performer. That was necessary. On a subway people will stare or look away. The audience [for DANIEL] must look,” without either gaping or refusing to see.

Parsons Dance is, in the words of its website, “acclaimed for delivering life-affirming, inspiring performances.” Seeing the fraught DANIEL in rehearsal, Omar notes, “David [Parsons] was very concerned. He was afraid people would hate it and wanted me to do something else. I refused. I needed to stay true.” In the final version, the hope and dedication of parents or anyone who deals with caring for another person’s was also celebrated, but the dark intensity of the underlying conception remained at its core.

“It was amazing, amazing, amazing, the audience reaction!” says Omar. “After it was done, I went through a breakdown for a little, crying for no reason. A year’s work was over.” He soon found a new direction with Ballet Hispanico. “My blood and my friends were there, but I was a bit detached. I wanted to get back in touch, make a bridge.” Luckily, the company needed a dancer mid-season, so Omar joined them for 8 months. “It was a great experience. I got to work with one of my favorite choreographers [Gustavo Ramírez Sansano], who created a piece on me.”

But ultimately, “Life was pushing me toward choreography.” Dancing full time with a company and making pieces for others at the same time “clashed horribly.” Omar got the Whim W’Him Choreographic Shindig IV commission even before starting with Ballet Hispanico and decided, “I need to go here. You can’t have it all. You need to make choices.” And so he has embarked on his career as a full-time choreographer.

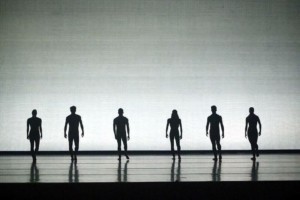

“Whim W’Him is so great!” Omar exclaims. The dancers are artistically mature. “They are all at a place where they can move forward quickly in the work.” He also loves how they are all so different from each other, in training, personality and approach to dance.

Coming into the studio, Omar had ideas, though they weren’t clear yet. “You’re not working with clay, but living beings. Who they are determined the theme.”

In crafting his new piece, he says, “I didn’t want the dancers necessarily to know too much” in the beginning. He told them his inspiration: depressive and bi-polar illness. “I have dealt with someone with it—and anxiety, we all deal with that.” The dancers, he says, “have rich movement. They could portray it all in movement, not facial expression.” With a smile he says, “Expression can be added in as needed, like cinnamon or vinegar.”

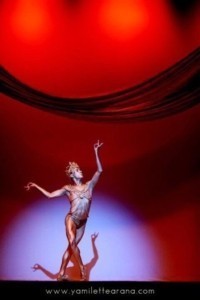

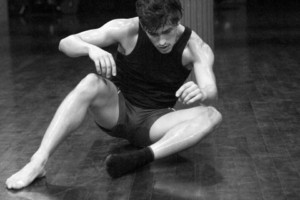

Photo credit: Last 3 images for Whim W’Him by Stefano Francesco Altamura