Growing up in Portugal, Bruno Roque “wasn’t in a dance world.” Though he went to “a traditional summer camp where they would host occasional dance/ball/prom kind of evenings,” did 4 years of martial arts, and loved the fifties American musicals he saw on film, “I never thought it was something I’d like to do.”

But then his mother Teresa enrolled in drama school when he was 12, working nights and going to classes during the day. She and her son scarcely saw each other. Bruno was an independent sort, he relates, and took it in his stride, “but looking back, it was rough on her.” So she found a novel solution by enrolling him in the National Conservatory of Dance, which was in same building then as the drama school. “A bit like Fame,” says Bruno, “Cinema, drama, music, dance.”

The abrupt transition was “a bit odd,” he reports, but “I didn’t mind change and my school was too far,” so he went along with the idea. When they were buying the things needed for dance school, he did begin to wonder, “‘What the hell am I getting myself into?’ But there was a lack of boys—there are more now—and I was accepted.”

Since he was 13, almost 14 by then—at that age, most students were already in year 4 of an 8-year dance program—”I was put into a class of inepts, an extra class for those with no background.”

Luckily perhaps, his first class was modern dance, rather than classical ballet, where his lack of preparation would have been more of a hindrance. “I fell in love,” he says simply. A flute, guitar or piano player accompanied each class. “I was fascinated by that.”

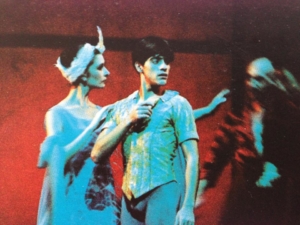

He was also naturally good at it. The main forms of dance at that time at the Conservatory were classical ballet (a bit more) and Graham-based modern, along with “everything else, like a normal dance school—notation, dance history, pas de deux.” Academic subjects provided a backup, just in case he decided that dance wasn’t the profession for him. But there were also dance workshops, “where young choreographers set new, small creations on the students. And that was what made me want to do this.”

Five years passed quickly. Bruno “paid a bit more attention to the Graham—I got it faster. But I haven’t discriminated from the beginning. I was open to both. It was a close race. I had moments of attraction to classical as I got better—I was the prince—but both were pretty balanced. I could see the special things of each.” He says he never saw himself a strictly classical dancer, thinking, “I’m not a dancer—it’s a limited label—I’m an artist.”

In his last Conservatory year, Bruno’s school performance in the 3rd act of Raymonda caught the eye of the National Ballet of Portugal director. “He liked me and suggested that I go on. Clearly I had the body and mind for it. He said, ‘We can try to find a scholarship for an extra year,'” to make Bruno a still better dancer. The choices were “School of American Ballet, Paris and St. Petersburg.” The Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet seemed the right choice then. “Though I don’t regret it, I might’ve made a different choice knowing what I know now.”

He auditioned, was accepted and was awarded a Ministry of Culture scholarship that paid a lot, $10,000 for year, though it didn’t provide living expenses. “St. Petersburg is a gorgeous city,” Bruno recalls, “but I only saw the sun for one day in the whole time., which was hard after Portugal—though later living in Belgium was worse. That time was rough, I was more alone I’d ever been.” He pauses before saying, “It’s good that I like to be alone.”

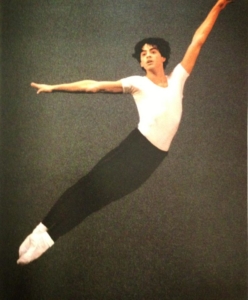

During his Russian year, “I got very physically strong and confident.” At the end of it his teacher said it would be good for him to do another year, but since it would have been without scholarship, he declined. “Thankfully, probably,” he now says. Instead he joined the National Ballet of Portugal. “There were lots of opportunities, more than usual, a nice rep, interesting contemporary work. I got to do a full length in the first year.” He adds with a smile, “It’s good baggage for a dancer, confidence.”

But there’s a Portuguese saying about standing “Back to Europe and facing the ocean.” After 5 years, that wanderlust got hold of him again. “I wanted to know if I could make it elsewhere and wanted to try more different things.” Professional curiosity, relationship considerations, and perhaps a general restlessness prodded him in his next career choices—2 years with the Royal Ballet Flanders in rainy Antwerp; another back at the Portuguese ballet, where he had lifetime tenure; then on to 12 years in Monaco.

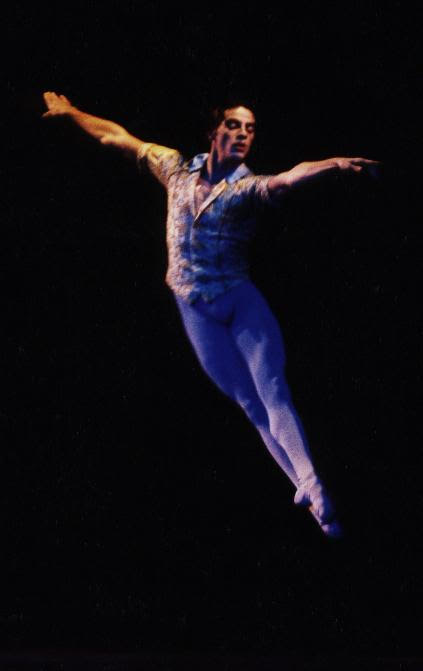

With Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo, Bruno’s vocabulary and opportunities as dancer expanded, he explored his own voice creating works himself, toured all over the world, and met his wife, dancer Noelani Pantastico, who now lives in Seattle (with Bruno), where she is back again as Principal Dancer at Pacific Northwest Ballet.

Of his Monte Carlo period, Bruno says, “Touring could be hard—it could get to be close quarters at times. But always I was grateful to go places. There were moments when, say, we arrived back from Mexico, did a load of laundry, and were off the next day to China. But I loved the touring life and wouldn’t trade that experience for the world.”

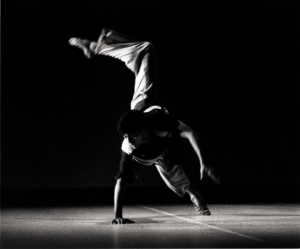

He also loved the opportunities to choreograph, though at first the idea was very daunting, since he has a great aversion to doing anything badly. In his 4th or 5th year at Monte Carlo, director Jean-Christophe Maillot held a young choreographers evening. Bruno, who was 26 or 27 at the time, applied. “I forced myself—I didn’t want to regret not having done it. The motivation was out of fear of regret.” But, somewhat to his surprise, “It went rather well, I got great feedback, and thought ‘I should do more of this more often.'”

I asked Bruno about the role choreography played in his decision to stop dancing. “I had tried to leave Monte Carlo for one reason or other before, but it didn’t work out—I needed it to be for something great,” he replied. After all, “I lived 100 feet from the Mediterranean, and there was all that travel. To be very honest, I felt that the director wanted to renew the company—he’d always preferred more mature, experienced, versatile dancers before. Then that changed. He was always very nice about it. We had a few talks. I was bit pushed, though I could have danced longer. In the end I just wanted to move on. Choreography helped to make the decision easier, but didn’t cause it.’

Bruno still travels a good deal, staging works for Jean-Christophe (for example, Romeo et Juliette in Montreal, Faust in Antwerp for his old company there, and Cendrillon at PNB in Seattle). He also has an increasing number of commissions for works of his own, including his current creation for Whim W’Him—but more of that in another post…