“Approaching Ecstasy is not a light, happy ballet,” writes Melody Datz Hansen, for City Arts, in a review entitled ‘The Delicate Balance of Beauty and Pain’: “The music is slow and haunting, the dancers’ movements are furtive and low to the ground. Weaving through the moving bodies onstage, a somber choral group chants 100-year-old poems about fate, sex and unrequited lust. This powerfully dark but ultimately uplifting multi-media performance, a collaboration between contemporary dance company Whim W’Him, choral group The Esoterics, the Skyros Quartet, harpist Melissa Achten Klausner and composer/conductor Eric Banks, closed among ‘wows,’ ‘ohs,’ and one whispered ‘goddamn’ from the opening night audience last weekend at Cornish Playhouse.”

A fair portion of the audience stayed on for the Q&A after the opening performance, asking good questions and getting frank and thoughtful answers from Eric, Whim W’Him artistic director Olivier Wevers and the dancers. One person wondered about the experience of the dancers who had performed in the original AE five years ago.

There were only two of them, Tory Peil and Jim Kent. Tory mentioned what the remake had meant for Olivier, allowing him to work with less of an eye to others’ reactions than to what he felt was needed in the work itself. Jim talked with relish about the 7 weeks for rehearsal this time: “It was a much longer process. Some parts had bothered Olivier before. Now he’s telling the story more fully. It was good seeing him play with it. It was not so much fun always last time—much more luxurious this time round.”

Olivier smiled. “There were parts I didn’t like. I hated ‘Obstacles.’ In the studio I said, ‘Forget it,’” and they started that one over from scratch.

Eric suggested that it was like a theme and variations and added, agreeing with Jim, “Olivier played with it—openness in a form that’s already there. It’s a better work now.”

Along similar lines, another questioner was curious about why they had chosen to mount this particular work again, since Whim W’Him is known for premieres.

“I’d said, Never again,” Olivier offered. “I was dreading it at first, dreading looking at the video. But when I began to dig back, I thought, I can make this better—richer and fuller. This time the dancers owned it.”

Eric expanded, “It was important to expend the effort. Time was needed to refine it.” In the course of this process, AE “went from a generative work to assessment and refinement. Seven weeks is so long!”

Laughing, Olivier said, “Before we were a pickup company with limited rehearsal time. I’d say, ‘We’ve got 3 hours to work and 2 people available. Okay, we’ll do a quartet’—or ‘There are 4 of you here today? Right, a duet.'” More seriously, he noted, “I learned about myself. I still have lots to learn but it’s going in the right direction. Eric too.”

“Yes,” Tory echoed Olivier, “this time, the dancers own it.”

As if in reply to that sentiment—when an audience member said, “This in an international piece. It should go around the world. I cried, it was so emotional. How do you—the dancers—feel about the emotion of it?”—Karl answered eloquently, “It is special to my life, struggling as a gay man. It is unfortunate what has happened in the world—in Chechnya or the Mid-East—and important to be aware of things outside our own context. It’s so easy to forget the rest of world while living in Seattle, with our dancers, leaders and audience here. I feel safe with them.”

The singers have to own it as well. The music, as one audience member observed, “Very complex.” Eric acknowledges that “Everything I write is complex.” He draws on music from multiple sources and was inspired here by the era of the poems and by the many cultural influences of Alexandria, where the Greek Cavafy lived—he used Arabic maqāmat (like Indian rāga, as he said) and spoke of “the irregular scales of Egypt,” and the unusual (at least for us) time signatures like 13/8 or 17/8 he employed in AE.

“I love the way the singers were integrated into the dance,” someone else contributed.” It’s hard for them,” Olivier said. “They don’t see me,” Eric noted of the 4 quartets who intermingle with the dancers. He conducts with his back to the audience and that half of his choir (of 32, down from 40 in the original version). They also sing a cappella the English versions of all the poems, which are “homophonic, written so that they’d be clear to each other.” And someone added, “To the audience too.” For Eric, who normally specializes in choral music, this work was a chance to venture into new territory—Melissa, the harpist, who was his student at Cornish at the time, “gave me lessons in how to write for harp.”

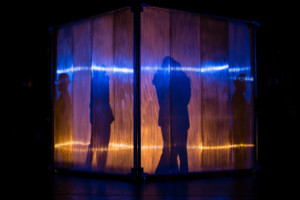

A number of comments were made about the set pieces, designed for the first production of AE by Casey Curran—particularly the dramatic, angled frame that descends for the mirror duet of Patrick Kilbane and Karl Watson to the poem called ‘In the Vestibule,’ its symmetry shattering as a young man merges with his reflected image.

Likewise, the dynamic stage presence of the large box, opened and closed by the dancers…

symbolized, at different moments, windows

or walls…

or a carriage in which a tryst is held, and so on.

“What is the kernel of the story?” a different questioner inquired. “The first time it was more segmented.” Olivier’s answer was, “I wanted a through line this time. Tory is the poet’s muse, the inspiring voice in his head that also drives him crazy. Sometimes she represents the poet himself [as do other dancers], and sometimes his soul.”

Illustrations of the various themes of the poems and the poet’s life (his double life, his love of beauty, his secret writings) abound throughout the piece.

“The irony is that his poetry is sung, while he lost his voice due to larynx cancer at the end of this life,” Olivier said, then continued, “All that is left then, at the end, is his hat,” which Tory tenderly carries out. “What we have now is Cavafy’s legacy, what he left, all the hats” that the singers lay down on the stage floor, before exiting 2-by-2, as they entered at the start.

In the future, in a more perfect world, the poet wrote,

Some fortunate man, created just like I am, will find himself

Able to live without shamefulness or hesitation, and be free.