“Anytime you buy a ticket to a performance, it’s kind of a crap shoot, right?” Marcie Sillman asks on her blog, And another thing… “You never really know what will happen, whether or not you’ll like the show, even if that show is something you see every year, like Nutcracker. That’s the joy of live performing arts. It’s an even bigger gamble when, say, you decide to see new works by three choreographers you’ve never heard of. That was the case this past weekend at Whim W’Him’s Choreographic Shindig.“

Writes Alice Kaderlan, for her online blog, Feet First in The Seattle P.I.: “One mark of a first-rate artist is the capacity to constantly change and grow, to push boundaries and limits. In this latest outing from Whim W’Him, artistic director Olivier Wevers demonstrates that he can do this even when he’s not choreographing. For this latest program Wevers has stepped back from creating dance works. Instead, he’s moved into the role of mentoring his seven dancers as curators, allowing them to select the three choreographers whose ballets they’re performing in what Wevers calls this Choreographic Shindig.”

Since the first weekend’s performances, I keep hearing about the Shindig—from dancers, audience members and critics: How distinct each of the company’s seven dancers is and how unlike the three current pieces. I never tire of watching the Whim W’Him dancers do series of movements in unison. You would never make a uniform classical corps de ballet out of this crew—they’re all dancer thin, but beyond that there’s a wide range of body types, training, movement styles and personalities. Yet somehow they click and make a convincing, often quite surprising ensemble. It’s variation within unity, harmony in difference.

Not surprising then, that such a diverse group of dancers would come together to choose choreographers so different in sensibility as Joshua Peugh, Maurya Kerr, and Ihsan Rustem. Truly something for everyone.

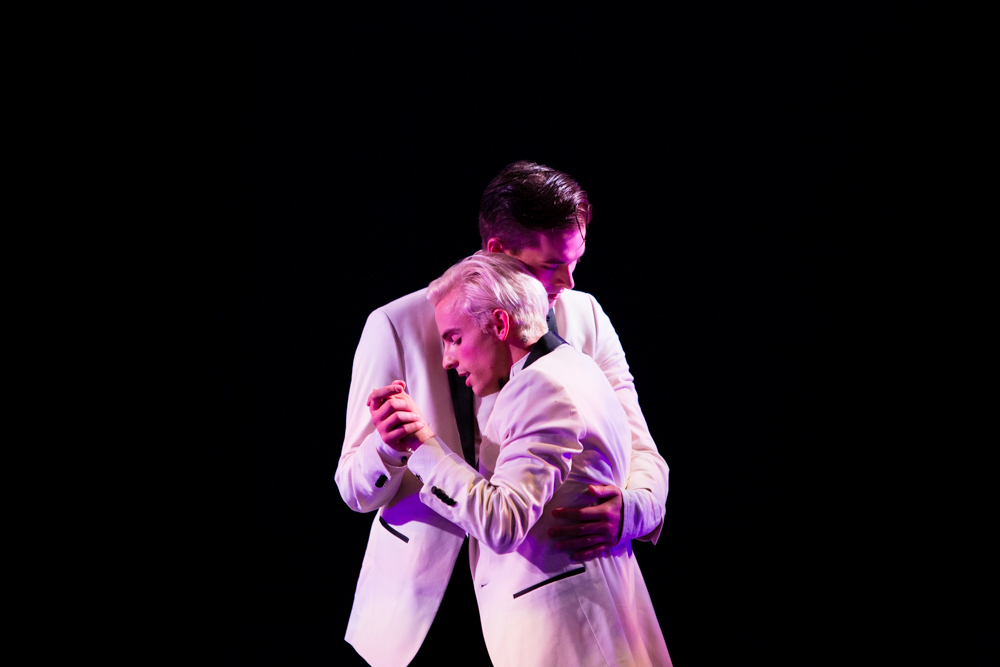

A case in point is the use by each choreographer, and to highly varied effect, of Tory Peil and Kyle Matthew Johnson in a key duet…

… from tentative young love through anguished confusion to complex understanding.

The opening work on the program, Short Acts on the Heartstrings In Marcie Sillman’s words, this “rumination on love and relationships, set to a medley of mainly mid-20th century pop ballads, was as light as the sea foam green chiffon dresses the three female dancers wore with their tan ankle socks. Light, sweet fun.” Sillman continues, describing the second piece on the program: “San Francisco-based choreographer Maurya Kerr’s offering, by contrast, was dark and brooding… into the wide welcome centered on a duet performed by Tory Peil and Kyle Johnson. Peil’s long, elegant limbs twitched and spasmed, a portrait of a creature who longs for human contact but whose body seemingly reacts against it. wide welcome had its moments, but in the end, it just felt a little murky.“ Because of scheduling complications, Maurya first met the dancers in March and then not again until about a week before the opening of the Shindig. In the meantime, having made three other pieces and undergone a stint in graduate school, her perception of her Shindig creation had changed so much that most of the material was scratched and a new conception choreographed. In Alice Kaderlan’s words: “Kerr, a former dancer with Alonzo King’s LINES Ballet, has been honored with several choreographic awards so “into the wide welcome” may not represent her strongest work.” The resulting piece does seem a bit of a work-in-progress, in the sense that some of the ideas might have more developed had there been more time, but there were indeed riveting moments, including the aforementioned duet, an interesting trio of couples, and a final mesmeric wave-like section.* [Please see end note.] The tagline for wide welcome is an enigmatic quote from Jenny Holzer: “It is in your self-interest to find a way to be very tender.” “Michael Upchurch writes of the piece for The Seattle Times: “Seattle native Maurya Kerr’s into the wide welcome—set on three male and three female dancers—is more severe. Floor-bound and undulating at first, the performers grow nearly unhinged in the leaps and swipes they take. They simmer, tremble, panic, erupt and flail … until their angst evolves, almost imperceptibly, into a kind of pulsing serenity.”* “Undulating,” “slithery,” “sinewy,” “sinuous,” “continuous.” These are the adjectives applied to Ihsan Rustem’s movements. Marcie Sillman writes about his piece: “The real highlight of Choreographic Shindig, the dance not to be missed, is Ihsan Rustem’s The Road to Here. Lyrical and physically demanding at the same time, this short gem has it all: strong performances by the entire company, inventive choreography, a touch of humor, but most of all, The Road to Here has an emotional resonance that sits with you long after the lights come up and the audience files out.“ According to Kaderlan, Ihsan’s “style requires great flexibility of the spine and upper body,” and she adds that “Rustem is particularly adept at using the ensemble to almost meditative effect. In the most compelling section, the four men step forward while the women, interspersed between them, step backward. Then they reverse their motion so that the women move forward while the men step back. Out of such simple actions Rustem is able to create spellbinding imagery that lingers in the mind and the eye.”* Meanwhile Upchurch writes: “Ihsan Rustem’s The Road to Here is a veritable powerhouse that plays with space and the nature of choice in crazy ways. It starts off with Peil and Johnson engaged in soft fluid contact acrobatics, before five other dancers join the intimate and continually morphing action. In the final stretch, the musical score gives way to a recording of Alan Watts asking, ‘Did you ever see a cloud that was misshapen? Did you ever see a badly designed wave?’ The dancers—sometimes humorously, sometimes hectically, always sensuously—seem to answer a firm ‘No.’ Lighting designer Michael Mazzola plays a key role throughout.“ While she was watching Ihsan’s piece, Sillman says, “I was thinking about the tuning fork that my third-grade music teacher had. She’d tap it, the metal would vibrate and produce a set of harmonic tones, and then she’d bring that fork close to our 8-year old bodies. You could feel the sound inside you. That’s how Rustem’s dance affected me. I could feel what he had to say through the choreography he created. “Normally I find the insertion of text into a dance a little off-putting. Either it’s too obscure (or I’m too linear) to figure out why the text is there. Or else, it seems like the artist is trying to bludgeon me with a MESSAGE. When a man starts speaking in the middle of the melodic score in Rustem’s dance, though, I was all ears. I can’t remember his exact words, but they melded seamlessly with the dancers’ movements. What that man had to say resonated with me the way Miss McNelly’s tuning fork did all those years ago. In an epigraph printed in the program, Rustem quotes Alan Watts. ‘Choice is the act of hestitation that we make before making a decision.’ Leap into the unknown, take a risk, this dance shows us. And that’s what we do every time we experience art. We buy our tickets hoping the investment will be worth it. In the case of Ishan Rustem’s The Road to Here, my gamble paid off big time.“ * Which brings up an anomaly in Kaderlan’s review. Tepid in her assessment of Maurya’s piece, she is justly complimentary of Ihsan’s fine creation, but in a principle example of what is good about his work, she seems to be describing precisely the last section of Maurya’s: “Rustem is particularly adept at using the ensemble to almost meditative effect. In the most compelling section, the four men step forward while the women, interspersed between them, step backward. Then they reverse their motion so that the women move forward while the men step back. Out of such simple actions Rustem is able to create spellbinding imagery that lingers in the mind and the eye.”

Upchurch also refers to that wave-like passage when he writes, “…until their angst evolves, almost imperceptibly, into a kind of pulsing serenity,” but he correctly attributes it to Maurya’s piece. I’m afraid that by quoting the misleading paragraph above in this post, I just perpetuated the confusion .